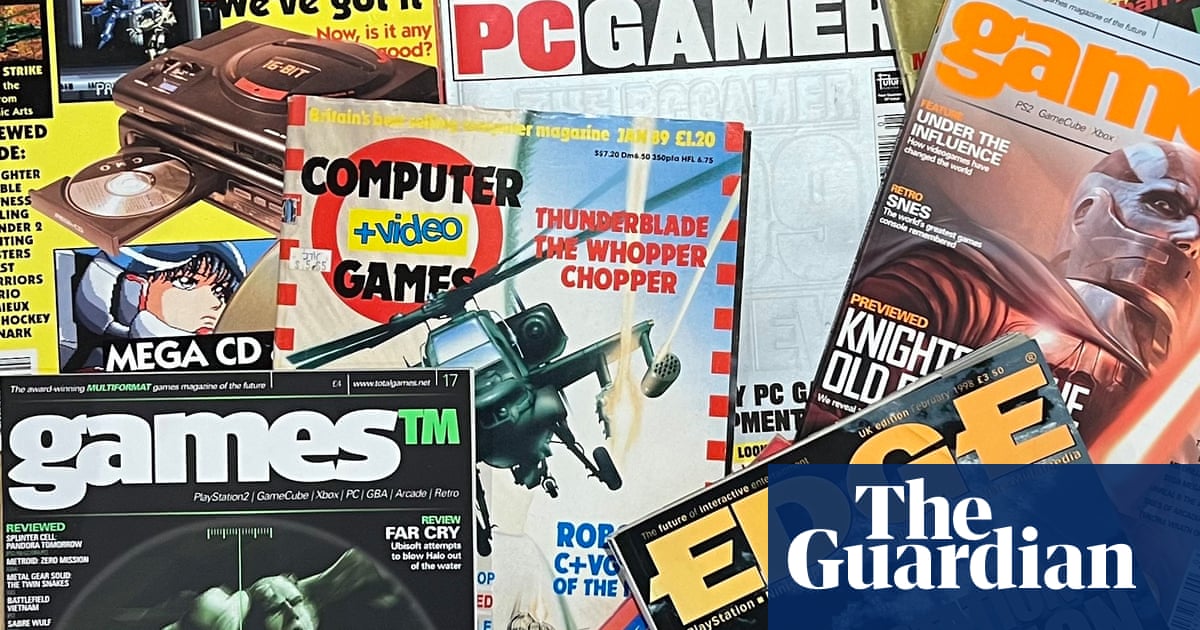

Before the internet, if you were an avid gamer then you were very likely to be an avid reader of games magazines. From the early 1980s, the likes of Crash, Mega, PC Gamer and the Official PlayStation Magazine were your connection with the industry, providing news, reviews and interviews as well as lively letters pages that fostered a sense of community. Very rarely, however, did anyone keep hold of their magazine collections. Lacking the cultural gravitas of music or movie publications, they were mostly thrown away. While working at Future Publishing as a games journalist in the 1990s, I watched many times as hundreds of old issues of SuperPlay, Edge and GamesMaster were tipped into skips for pulping. I feel queasy just thinking about it.

Because now, of course, I and thousands of other video game veterans have realised these magazines are a vital historical resource as well as a source of nostalgic joy. Surviving copies of classic mags are selling at a vast premium on eBay, and while the Internet Archive does contain patchy collections of scanned magazines, it is vulnerable to legal challenges from copyright holders.

Thankfully, there are institutions taking the preservation of games magazines seriously. Last week, the Video Game History Foundation, a non-profit organisation dedicated to the preservation of games and their history, announced that from 30 January, it would be opening up its digital archive of out-of-print magazines to read and study online. So far 1,500 issues of mostly American games mags are available, as well as art books and other printed ephemera, but the organisation is busy scanning its entire collection. The digitised content will be fully tagged and searchable by word or phrase, so you’ll be able to easily track down the first mentions of, say, Minecraft, John Romero, or the survival horror genre.

In a recent video introducing the archive, VGHF librarian Phil Salvador explained: “We wanted to make something that’s going to be useful and easy for anyone studying video game history, whether you’re an academic writing a book or a creator making a YouTube video, or you’re just a curious person.”

Founded by game historian Frank Cifaldi in 2017, the VGHF is part of a growing number of archives, academic institutions and museums dedicated to preserving games history. While the focus is usually on tracking down and preserving the games themselves, there is a growing understanding that magazines provide vital context. “Video game magazines are often representative of people’s relationships to video games – they accompany that journey,” says John O’Shea, creative director and co-CEO of the National Videogame Museum in Sheffield, which has a growing collection of printed materials. “They have a similar lineage to football and music fanzine culture, in that they provide perspectives on the players and the fans and what they were thinking at the time. They also provide insight into particular trends and narratives, what gets emphasised, what doesn’t. They provide direct access to a particular historical period.”

Magazines then tell a sociocultural story that the games themselves cannot. “Looking at these magazines now, through the lens of contemporary video game culture, it’s not just what is there, but what is not there,” says O’Shea. “The majority of characters featured in magazines up to the early 2010s are men. I looked at a selection of PC magazines from 2011 and there were the same number of female protagonists represented as there were panda protagonists.”

Games mags were often written for very specific, very dedicated demographics, and reflected the focus of the industry itself. Many adverts throughout the 90s and into the early 00s featured skimpily dressed women, even when the games were military shooters or strategy sims. Classified ads for premium rate video game tips lines were accompanied by photos of women in bikinis. “It’s there because that was the demographic they were aiming at – teenage boys,” says the museum’s collections officer, Ann Wain. “The marketing shows who was getting the attention and why. The letters pages also tell us a lot about player culture. What topics were people discussing, what was the conversation around games. It contextualises games in a way that just playing them can’t.”

Both the VGHF and the National Videogame Museum are reliant on donations: the latter has just received an almost complete collection of PC Gamer from a collector who also kept all the cover demo discs and inserts. It’s important work because often the magazine publishers themselves have patchy records on preservation. Future Publishing does have an archive at its Bath office but it is not complete, and whole collections have been lost when other companies have shut. In a post on LinkedIn last year, veteran games media publisher Stuart Dinsey recalled that when he sold Intent Media in 2013, the new owner pulped almost the entire back catalogue of its industry publications CTW and MCV.

after newsletter promotion

Looking back on video game history, it’s easy to imagine a smooth narrative flow, a sense of inevitability about which games or technologies would be successful and which would fail. But it wasn’t usually like that: contemporary reporting reveals a mass of complications and uncertainties. “Video game magazines provide a lot of resistance to that very linear idea of history,” says O’Shea. “Especially the technologically deterministic view that more powerful tech would inevitably be more interesting and successful”.

When you go to the VGHF’s digital archive next month, look at contemporary news around the Sega Mega Drive, the original PlayStation or the Nintendo Wii – there was no agreement at the time over their impending success. Games mags were on the frontline of games history. In this uncertain era for the industry, their voices, dimmed and distant though they seem, are more important than ever.