This essay was adapted from Kevin M. Levin’s newsletter, Civil War Memory. Subscribe here.

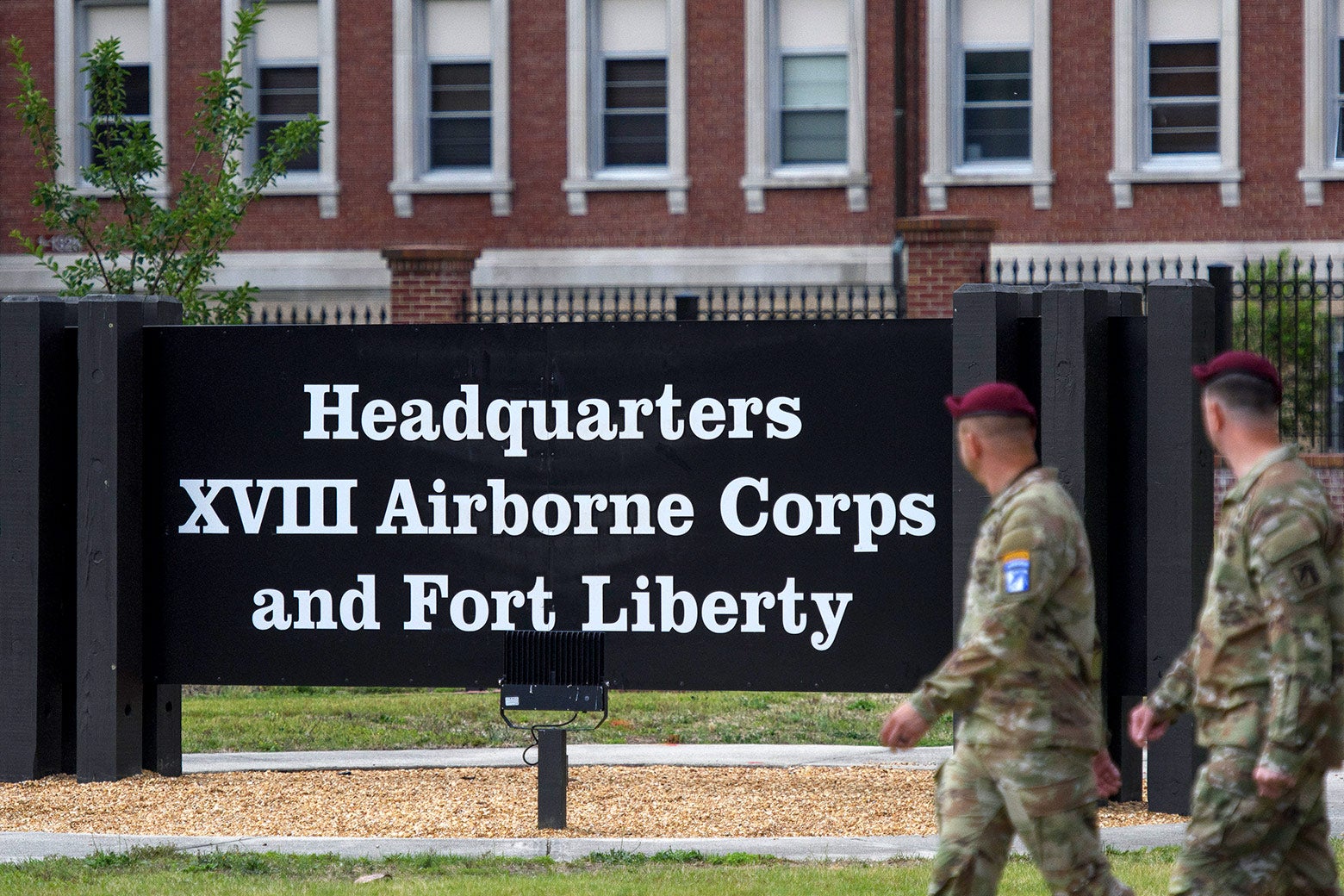

On Monday night, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth signed a memorandum renaming Fort Liberty, in North Carolina, back to Fort Bragg. This comes after a congressional committee recommended in 2021 that the fort, named for Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg, be changed to Liberty, as part of a wider effort to eliminate military honors bestowed on individuals who rebelled against the United States during the Civil War.

Donald Trump campaigned in part on a promise to restore the name of Fort Bragg.

Mission accomplished.

Members of the Confederate heritage community placed their faith in Trump to restore the honor and respect that they believe should be accorded their ancestors.

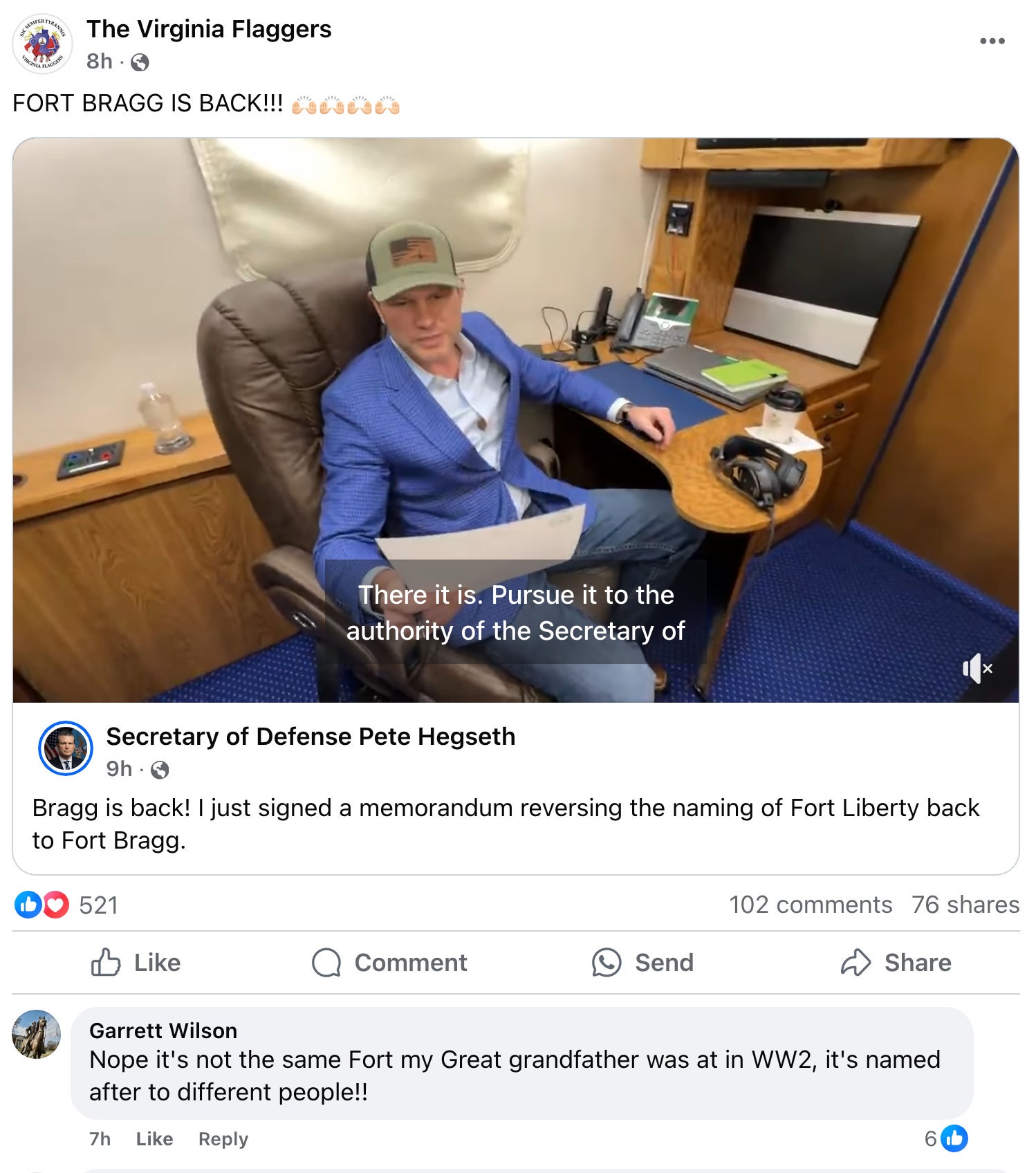

On hearing the announcement, the Virginia Flaggers, a group organized in 2011 to combat calls to remove Confederate symbols from public spaces, celebrated by posting a video of Hegseth signing the memorandum. But as you can see from the first comment here, not everyone is happy about it.

Other commenters chimed in as well:

“It’s not Ft Bragg, as in General Braxton Bragg. He’s playing fast and loose with the truth!”

“It’s not the same. It was named for a WW2 PFC because he had the same last name as General Bragg.”

“Instead of renaming it after Confederate general Braxton Bragg it is renamed in honor of private Ronald Bragg, a WWII private. Quite the sleight of hand and an insult to the memories of the Confederate American veterans and all of the ancestors who fought and served in every war this country has ever been involved in.”

Others suggested that this was an acceptable compromise, given that Congress has banned the naming of federal military installations after Confederate leaders.

In contrast, one camp of the Sons of Confederate Veterans is describing the renaming as a “political bait and switch.”

And yet another wrote:

The fort will be renamed to honor Pfc. Roland L. Bragg, a World War II hero who earned the Silver Star and Purple Heart for his exceptional courage during the Battle of the Bulge in 1944. This namesake, I believe, is an improvement over the former Bragg, who is remembered for his poor temper and combative personality, and who briefly commanded the Army of Tennessee to partial victories at Perryville, Stones River, and Chickamauga before resigning in November 1863.

To be honest, I can’t stop laughing. Those in the Confederate heritage community got played. They placed their faith in a corrupt Northern businessman—the very thing their antebellum Southern ancestors feared.

They should have seen this coming.

The Lost Cause, a pro-Confederate narrative that frames the war as a defense of states’ rights, “loyal slaves,” and heroic Christian warriors, occupied a central place in the nation’s collective memory for much of the 20th century. The display of Confederate symbols in prominent public spaces remained largely unchallenged by both Democrats and Republicans as recently as the 1990s. In recent years, Democrats, as a result of their embrace of a more progressive agenda, have led the fight calling for the removal of symbols celebrating the Confederacy in public spaces, but even Republicans have gradually begun to distance themselves from the practice.

In 2010 Virginia Republican Gov. Robert McDonnell signed a proclamation declaring April “Confederate Heritage and History Month.” Protests ensued over the proclamation’s failure to acknowledge slavery as central to the war and the Confederacy, as well as its strong Lost Cause overtones. In addition to issuing an apology, McDonnell promised to sign a new proclamation the following year, which he did, declaring April “Civil War History in Virginia Month.” The proclamation recognized slavery as an “inhumane practice” and the Emancipation Proclamation as having “ended its evil stain on American democracy.”

In 2015, just weeks after the horrific murder of nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, by a white supremacist, the state’s Republican governor, Nikki Haley, called for the removal of a Confederate battle flag that had flown on the Statehouse grounds since 1962. Haley had previously embraced the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who viewed the flag as a symbol of “heritage” and not as a symbol of racism. She had bent over backward to reassure its members that their flag would not be removed, but in the wake of the murders and the publication of photographs of Dylann Roof posing with a Confederate flag, Haley and much of the Republican state Legislature voted to remove the flag once and for all.

Despite speaking out on occasion praising generals like Robert E. Lee and calling for laws to protect Confederate monuments during his first term, Trump did little in his capacity as president to turn the tide, and there is little reason to think he will do so during his second term.

For example, the memorandum that Hegseth signed failed to mention a single word about the man the fort was first intended to honor.

There are eight other military bases, whose names once honored Confederate leaders like Gens. Lee, George Pickett, and John Brown Gordon, that could be restored in defiance of Congress. That, however, will be more controversial, as they (unlike “Fort Liberty”) were renamed after U.S. military heroes. Anything is possible, though it will be difficult to find appropriate substitutes for some of these names.

While I don’t want to see Fort Gregg-Adams, the base in Virginia that once honored Lee and now honors Lt. Gen. Arthur J. Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams, changed back to “Fort Lee,” I can only imagine how the SCV and others would respond to a re-renaming after any Lee other than their holy Confederate chieftain.

For now, it is enough to watch the Confederate heritage community get trolled by the very people it hoped would turn the tide and restore Confederate symbols to their rightful place.

This clearly isn’t going to happen. It is yet another nail in the Lost Cause coffin.