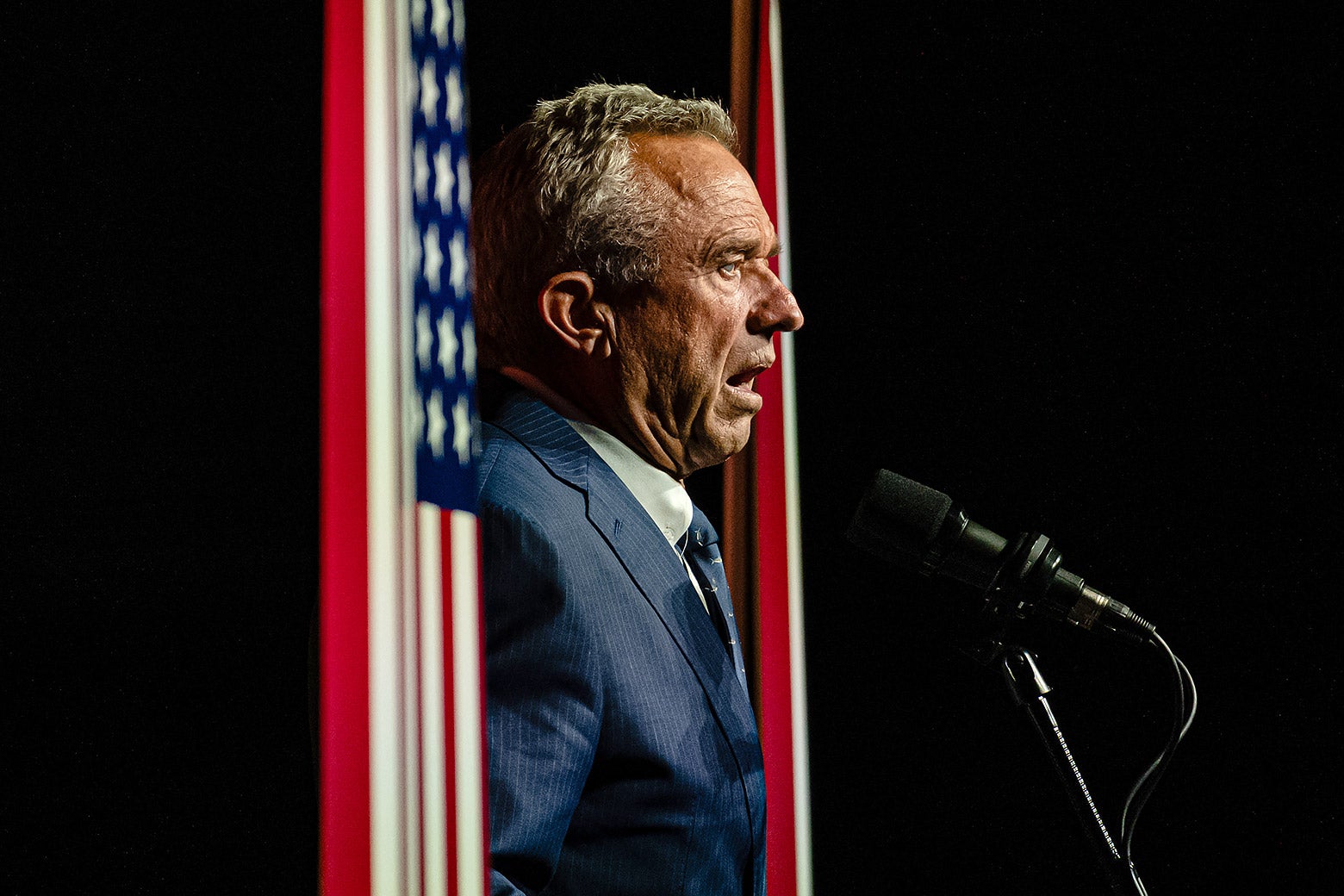

It’s difficult to fully comprehend the degree to which so many Americans seem to have gone down conspiratorial rabbit holes over the past decade, and the degree to which conspiracy theories have become mainstreamed into American politics thanks to Donald Trump and his MAGA movement. Trump’s incoming staff and his Cabinet nominations reflect this troubling development, with Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s nomination for director of Health and Human Services most encapsulating the turn not just to the conspiratorial but toward a mishmash of social, political, and cultural beliefs that defy partisan classification. After all, just over a decade ago, conservatives were losing their minds over Michelle Obama trying to get kids to eat vegetables and move their bodies; now Trump, himself an avid fast-food consumer, is elevating a raw-milk enthusiast who thinks fluoridated water is dangerously chemical.

Liberals are rightly incensed about the Kennedy nomination. This is a guy who has promoted the deadly and widely debunked theory that vaccines are linked to autism and other health issues, despite overwhelming scientific and medical evidence that vaccines are not only safe but perhaps the biggest public health victory of the past century, saving millions and millions of lives worldwide. Water fluoridation, too, has brought uncountable health benefits, especially for children.

But there’s a reason Kennedy’s views on health hold such appeal, and it’s not because the U.S. is a land of crazy people (it’s not). It’s because Americans can look around and see that something is very, very wrong with us: Three-quarters of Americans are overweight or obese, including almost half of teenagers and young adults; 1 in 5 children is obese; and rates of related diseases (diabetes, heart disease, and so on) remain astronomically high. We can see that our communities are saturated with fast-food and fast-casual chains, that even small children have mobility issues because of their size, that desperate Americans are turning to drugs like Ozempic in enormous numbers, and that being obese or overweight are not equally distributed: Wealthier, better-educated people tend to be thinner and healthier, while poorer Americans are not just larger and visibly less fit but actually sicker and likely to die much younger. We can see that this is about not just a lack of health insurance but also the building blocks of our bodies—the food we put into them, and the way Frankenfood products have replaced so much of what humans have traditionally eaten.

In the past few years, though, progressives have ceded skepticism of Big Food to the thoroughly anti-science right. We have left a hole here. People like Kennedy have filled it.

Liberals were, in the not-so-distant past, the cohort skeptical of Big Food and Big Pharma and the group concerned with the health and environmental consequences of how Americans eat, medicate ourselves, and move. The environmentalist movement of the 1960s and ’70s was intertwined with various healthy-eating trends, from veganism and vegetarianism to macrobiotics. More recently, bestselling authors like Michael Pollan have encouraged Americans to eat fewer processed foods, less meat, and more vegetables. Michelle Obama’s aforementioned “Let’s Move!” program encouraged schoolchildren to exercise while seeking to ensure they got some fresh vegetables along with their cafeteria sloppy Joes and tater tots—and faced enormous conservative blowback. Not so long ago, liberal cities were instituting soda taxes and mandating nutritional information on restaurant menus.

But the progressive tides turned. Obama and Pollan are now deemed problematic, as is the entire concept of obesity, along with the very idea that what we eat may indeed shape our body size or that body size affects health. Soda taxes are regressive and unfair to poor consumers, while nutritional information is a pretext for shaming. We trust the science, except when the science says things we don’t like, and in that case, the science is biased and wrong. Things are clearly much more complicated than “fat = unhealthy” or body mass index being a determinant of health or obesity being some line between healthy and unhealthy or weight loss amounting to nothing more than “calories in/calories out.” We are still understanding just how processed foods disrupt our systems, exactly how size and health interact, and just why Americans have grown so much larger in recent decades. But when it comes to food, weight, and health, a kind of science denialism has taken hold among the podcast set of politically engaged educated liberals. Since this cohort tends to be the one staffing Democratic campaigns and offices, and since big food companies are generous political donors to Democrats and Republicans alike, it also seems as if the Democratic Party as a whole has moved away from the Obama-era focus on whole-body health.

The Republican Party is significantly worse, and even more beholden to Big Food and Big Ag. The first Trump administration scaled back the Obama-era efforts to make school lunches healthier, and reapproved a potentially dangerous pesticide Kennedy has explicitly campaigned against. But without Democrats’ countering, a lane has opened up for kooks like Kennedy, who are ostensibly liberals but have unpredictable patchwork politics. Those patchwork politics are exactly why people like Kennedy are appealing, and successful: They pull people in by saying what is plainly true—that the way we eat is clearly making us sick and even killing us, and that this trend has been enabled by our political leaders and denied by too many on both sides of the political aisle—and after embedding that hook, it gets infinitely easier to convince followers of increasingly fringe health claims.

It doesn’t help that at least some of what was once written off as wellness woo-woo—the benefits of yoga and meditation, a fear of microplastics, skepticism of pesticides and food dyes, doubts about the alleged safety of overinjecting animals with hormones and antibiotics then eating them—is increasingly bolstered by scientific research. The reality that the hippies and the health-food nuts were right about at least some things, and that the government and big businesses failed (and continue to fail) to adequately protect the public, can leave people understandably wondering which now-kooky ideas may in fact be seen as prophetic later on.

And it also doesn’t help that the COVID pandemic sent public health polarization into overdrive—and revealed big hypocrisies in the aftermath. As conservatives chafed at public health measures, including masking and school closures, liberals rallied (again, laudably) in favor of what public health experts advised. But as more information emerged, we were often too slow to recalibrate, and routinely resistant to information that conflicted with our politics. (As someone who favored school closures beyond when many public health leaders and European countries had deemed them necessary, I include myself in this group of people who got a lot wrong because of my own political biases.) Many believe-the-science progressives remain in denial about the real damage of things like school closures and widespread shutdowns, which extracted costs, including learning losses, social dysfunction, crime, and the decline of physical and mental health. And that the same progressives who closed schools and were incensed about mask-mandate violators gathered in huge crowds to protest police violence (protests that I believe were good and necessary) read to many Americans not as righteous but as deeply hypocritical.

Health for liberals, in the COVID era, became about vaccines and medications and insurance and hospital care—all absolutely crucial, to be clear, for public health and well-being. But other factors, including how and what we eat, how we move, and the environmental toxins we come into contact with, also shape our health, often in much more foundational ways than in-hospital treatments. And yet there has been no recent major left-wing push to better regulate Big Food, or to get healthier food onto the public’s collective plates, or to tie infrastructure to physical health. (Walkable cities, for example, make for healthier populations.)

There has also been a notable reticence to look squarely at the race and class dynamics at play. America’s least healthy and poorest states are also those with the highest obesity levels, and overweight and obesity are much more common among the lowest-income Americans than the highest. This may also account for some of the progressive blinders on this issue: The liberals writing about culture and politics, working for Democratic politicians, and formally and informally setting progressive intragroup norms tend to be college-educated and living among others like them in large cities in liberal states with easy access to healthy and fresh food. That no doubt shapes how much of an emergency they believe food policy to be and how much they’re personally affected by it.

In a nation (and a world) where so much of what we touch, inhale, and put in our bodies is processed, plastic, or polluted; where we can see with our own eyes the enormous generational changes in people’s bodies; and where the liberals and progressives who once fought against the big companies that are making us sick and likely changing how our bodies function have decided to stand down or are being overtly hypocritical, it’s no wonder that men like Kennedy who both say the obvious and claim to reveal hidden agendas have widespread appeal. But it’s also a sign of an enormous failing from the left. As the Democratic Party rebuilds itself in the wake of Kamala Harris’ loss and the political realignment that caused it, it should again brand itself as the party that protects the public from predatory corporations and prioritizes good health—which means being the party that takes on Big Food, and takes what we eat a whole lot more seriously.