It was just a community theater group adaptation of The Diary of Anne Frank, but the night of the performance took a chilling turn in the small town of Fowlerville, Michigan. On November 12, while the cast was on stage and the audience of some 75 people was in their seats, a handful of masked men loitered menacingly outside the venue. With their right arms outstretched in the fascist salute and a few black swastika flags waving in the breeze, they shouted, according to the testimony of a passerby: “Heil Hitler. Heil Trump.” A few days later, it was in Columbus, Ohio, where a dozen men, also with their faces covered and carrying red swastikas on black cloth, marched through the streets while making racist, xenophobic and anti-Semitic comments.

The two events are just a sample of the growing activity of the far right in the United States following Donald Trump’s electoral victory. “It’s clear that these groups, like the one that marched in Ohio, the Proud Boys, Patriot Front, White Lives Matter and more, are emboldened and very happy about the election,” Wendy Via, president and founder of the organization Global Project Against Hate and Extremism (GPAHE), which monitors extremist movements at national and transnational levels, explains via video call.

These days, the clearest evidence of the far right’s emboldening can be seen online: “They’re speaking more freely about their neo-Nazi and white supremacist messages,” says Via, from Montgomery, Alabama, based on her decades of experience studying and analyzing the intersection of technology and the far right. In a GPAHE analysis of posts on 4chan, the social network of choice for the American far right, words like “deportation,” “rounding up,” and “self-deportation,” among others, peaked during election week.

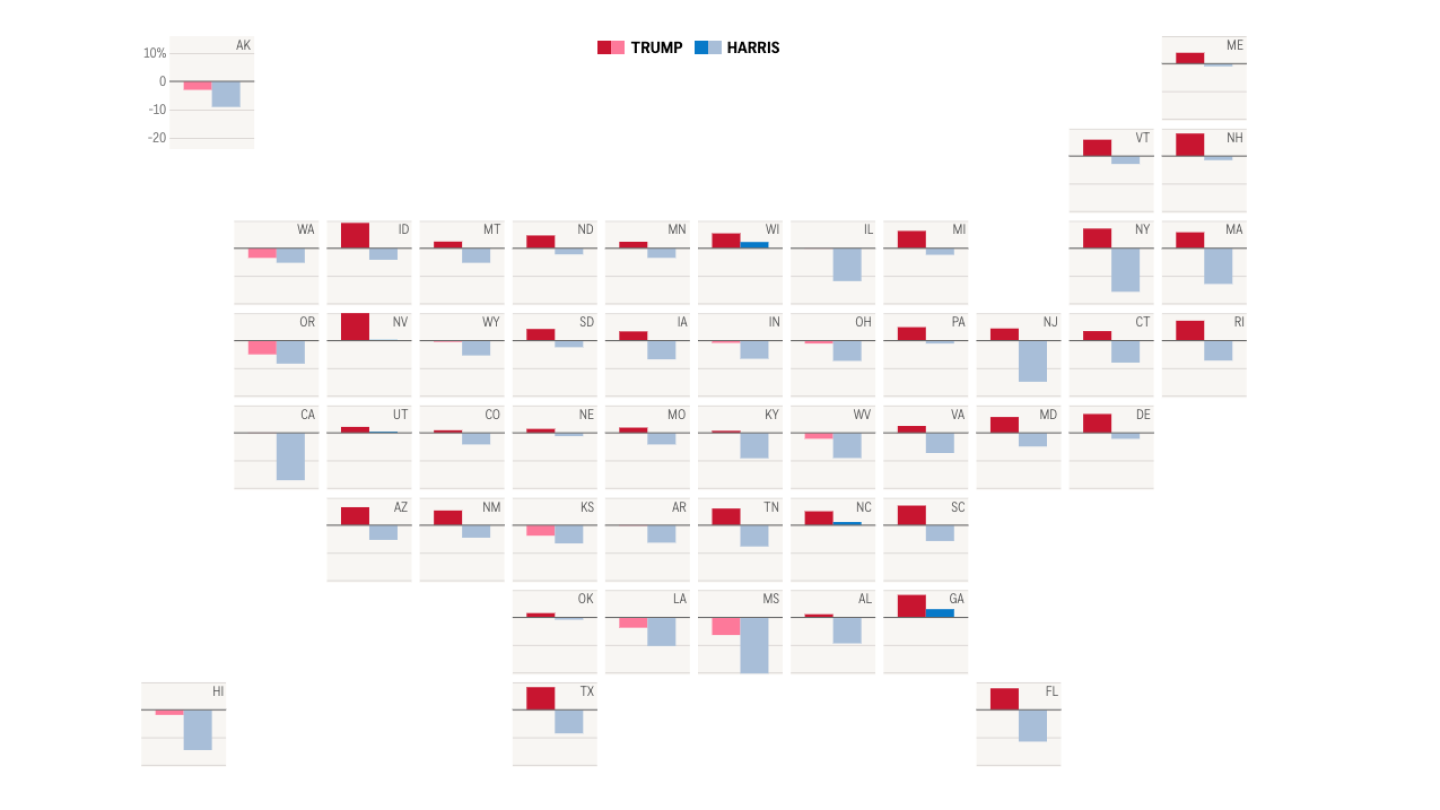

The organization’s report indicates that in the first 12 days of November there was a 40% increase in this type of rhetoric compared to the entire month of September. Another comparison: between August 8 and September 17, there were an average of between 400 and 600 mentions of this type on the platform per week; in the week of the election, this figure shot up to more than 2,400 mentions, an increase of 380%.

Even so, some of the more organized groups do not necessarily see the president-elect and his MAGA movement as representing them, as Joshua Fisher Birch, an expert on neo-Nazi and supremacist groups at the Counter Extremism Project, explains via video call from New York. “Trump is, in fact, heavily criticized by the far right for his support of Israel and his ties to the Jewish community,” he explains, “which is who they see as the ultimate global enemy, responsible for all the evil they imagine they face in the world. For many, Trump is the other side of the same coin.”

Still, even these extreme groups among the extremes share the president-elect’s authoritarian and xenophobic tendencies, and when he makes claims that immigrants “poison the blood of the country,” it is a veiled message to them. “If there is one policy that most of these groups are very excited about, it is mass deportations. The intersection with xenophobia is very important, and these groups are likely to recruit there,” Fisher elaborates. One possible scenario he poses is that the Trump administration does not fully fulfill its promise to deport millions of immigrants and these groups take advantage of this situation to sell the idea that only they, with their methods, can do it. “Mass deportation will be central to the far-right’s messaging in the coming years,” Fisher confidently predicts.

Another, more pragmatic reason why neo-Nazi and supremacist groups are happy about Trump’s election is that they expect less government surveillance. “They welcome the potential cuts to the FBI and federal law enforcement. They think that if there are cuts in funding and personnel, and also a change of approach, it could be good for them. It’s an important point that these groups are thinking about this,” explains Fisher, who spends his days immersed in the virtual world of the far right, from blogs to official websites and social networks.

“They claim that women should not have access to contraception, that they should not work, and even that women should not have the right to vote. They are no longer just talking trash, but suggesting violent scenarios around women.”

Wendy Via

It is precisely in this ecosystem where the misogynistic dimension of the 21st-century far right has become evident as a way of differentiating it from its predecessor ideologies of the last century, whose machismo was, at the very least, less explicit. Wendy Via explains that it is in this rhetoric where the greatest growth has occurred: “They say things like, since abortion laws are being restricted in some states, women should not have access to contraceptives; that women should not work, but stay home with the children; some even say that women should not have the right to vote. And they have reached the point where they are no longer just talking trash, but suggesting violent scenarios around women.” On 4chan, in the days following the election, users gloated over Trump’s victory and even “joked” about forming “rape squads” in response to the disappointment of young women who massively supported Harris.

In general, what experts like Via identify is that a climate of acceptance has been generated for some of the most extreme ideas defended by neo-Nazis and white supremacists. “They are going to go out to the squares and march to draw attention to themselves. They want to spread the word and they want to show that it is okay to think like them. And of course, we live in the United States, and there is freedom of expression and freedom of symbols. So it is their right. And they are exploiting their rights to generate fear in the community and let the people of the country know that they are on standby.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition