Babies with severe spinal muscular atrophy lack sufficient proteins to maintain motor neurons.Credit: YsaL/Getty

A two-and-a-half-year-old girl shows no signs of a rare genetic disorder, after becoming the first person to be treated for the motor-neuron condition while in the womb. The child’s mother took the gene-targeting drug during late pregnancy, and the child continues to take it.

The “baby has been effectively treated, with no manifestations of the condition,” says Michelle Farrar, a paediatric neurologist at UNSW Sydney in Australia. The results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine yesterday.

The child was conceived with a genetic condition known as spinal muscular atrophy, which affects motor neurons that control movement, and leads to progressive muscle weakening. About one in every 10,000 births have some form of the condition — making it a leading genetic cause of death in infants and children.

In its most severe form, as in the case of this child, individuals lack both copies of the SMN1 gene, and have only one or two copies of a neighbouring gene, SMN2, that partially compensates for that deficiency. As a result, the body does not produce enough of the protein required for maintaining motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. This protein is most important in the second and third trimesters, and the first few months of life. Babies with severe disease don’t usually live past their third birthday.

In the past decade, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three drugs to treat newborns for spinal muscular atrophy. The oral drug used in this study, called Risdiplam, manufactured by biotech firm Roche, based in Basel, Switzerland, is a small molecule that works by modifying expression of the SMN2 gene so that it produces more SMN protein.

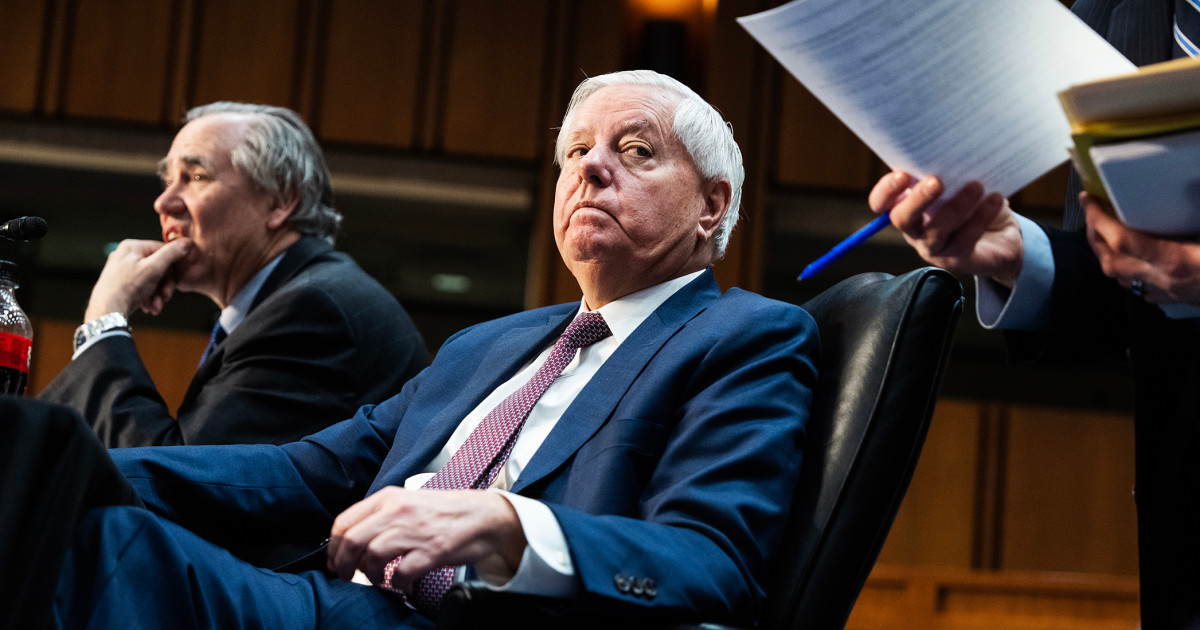

Up until now, treatments for spinal muscular atrophy were given after birth. But up to half of newborns lacking both copies of the SMN1 gene and with only two copies of the SMN2 gene are born with some symptoms. “There was still room for improvement,” says Richard Finkel, a clinical neuroscientist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, who led the study.

Parent proposal

The idea of giving the drug in utero came from the parents, says Finkel. “They had already experienced a loss from this horrible disease,” he says, and wanted to know whether there were treatment options they could start before birth. The FDA approved the study for this one individual.

The mother, who was 32 weeks pregnant, took Risdiplam daily for six weeks. The baby started taking the drug from roughly one week old, and will probably continue to take it for the rest of her life.