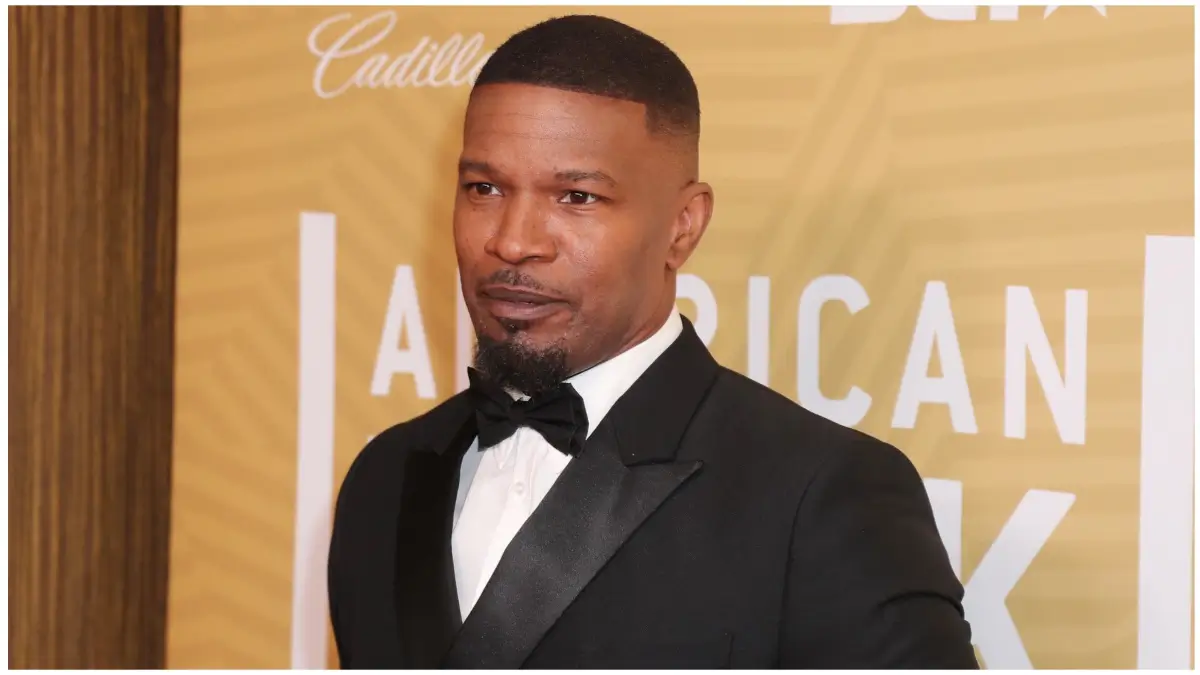

Bill Anderson, Chairman of the Board of Management of Bayer AG

In a bold move to restore $540 million in cost savings, Bayer CEO Bill Anderson cut out most of the company’s management roles last year. Since taking the helm in 2023, Anderson’s maneuvers replaced traditional management with a new operating model, called Dynamic Shared Ownership, or DSO.

In March of 2024, the company slashed half of its executive positions. Anderson’s DSO system asked employees to organize themselves into 90-day work sprints, via self-directed teams, and eventually 5,500 management positions were eliminated. Unfortunately, a year after the rollout of DSO, Bayer’s headaches remain.

When Management Cuts Aren’t Enough

“Rather than a lumbering corporation, Bayer will emerge as agile and bold as a startup—but one with operations in more than 100 countries. I’m convinced that this dramatic change will accelerate and unlock the value creation in each of our businesses,” Anderson ambitiously wrote in an article for Fortune last March.

According to Yahoo!Finance, Bayer’s market cap has fallen more than 44% this year. The stock price hit a 20-year low last November. Slashing management jobs, in Bayer’s case, didn’t yield the intended results. Why?

The answer lies inside the complexities of a global business, where a reduction of 5% of the workforce isn’t enough to change market conditions – or prior business decisions. Anderson’s push for autonomy may still be the hero of this story; it’s too soon to tell. But one thing is for certain: As the company reports a $4.1 billion net loss and adjusts its profit forecast downward, there’s more than one villain.

Reducing Management Jobs: A Cautionary Tale

While advancements in artificial intelligence and automation have influenced workforce dynamics across various industries, Bayer’s restructuring appears primarily driven by a strategic imperative to reduce costs. The company projected that these measures would contribute to €500 million ($540 million) in cost savings by 2024 and €2 billion ($2.16 billion) by 2026, according to BioSpace.

Bayer is still reeling from the 2018 acquisition of Monsanto, the manufacturer of RoundUp weedkiller (a product that has faced a steady stream of lawsuits, claiming the product causes cancer). So far, Monsanto is a $63 billion albatross that has failed to fly.

The company offers a complex portfolio, from aspirin and agriculture to Xarelto. Inside a worldwide distribution network, global shifts can have a big impact on the company. Nevertheless, efficiencies are at an all-time high, in various divisions, and Anderson says the company is embracing the self-directed leadership model. For example, the company’s pharma division, based in Italy, has cut product release times by 50%. Self-directed teams seems like an innovative idea. But sometimes, and this time, restructuring and layoffs are not enough.

Reducing bureaucracy increases efficiency, and maybe making the management cuts was the right idea. But restructuring hasn’t been enough to turn efficiency into positive investor sentiment – or profit.

When Cutting Your Workforce Fails to Save the Bottom Line

Competitive headwinds, market conditions and previous investments may be beyond a company’s control. But reducing the workforce, and restructuring, always is. Getting rid of management is a strategic move but, with a company that has over 95,000 employees and operates all over the world, many factors contribute to the company’s fortunes — or misfortunes, as the case may be. Anderson needs time to prove out his approach.

The market’s reaction to Bayer’s restructuring and financial performance has been cautious, at best. Efforts to cut managerial positions and streamline decision-making have so far had little impact, leading shareholders to demand more substantial actions from the CEO. Like Bayer, many companies are looking to restructure and eliminate middle management jobs and cut back on bureaucratic executive positions. The cautionary tale of Bayer reminds us that management layoffs may not be enough to turn things around.