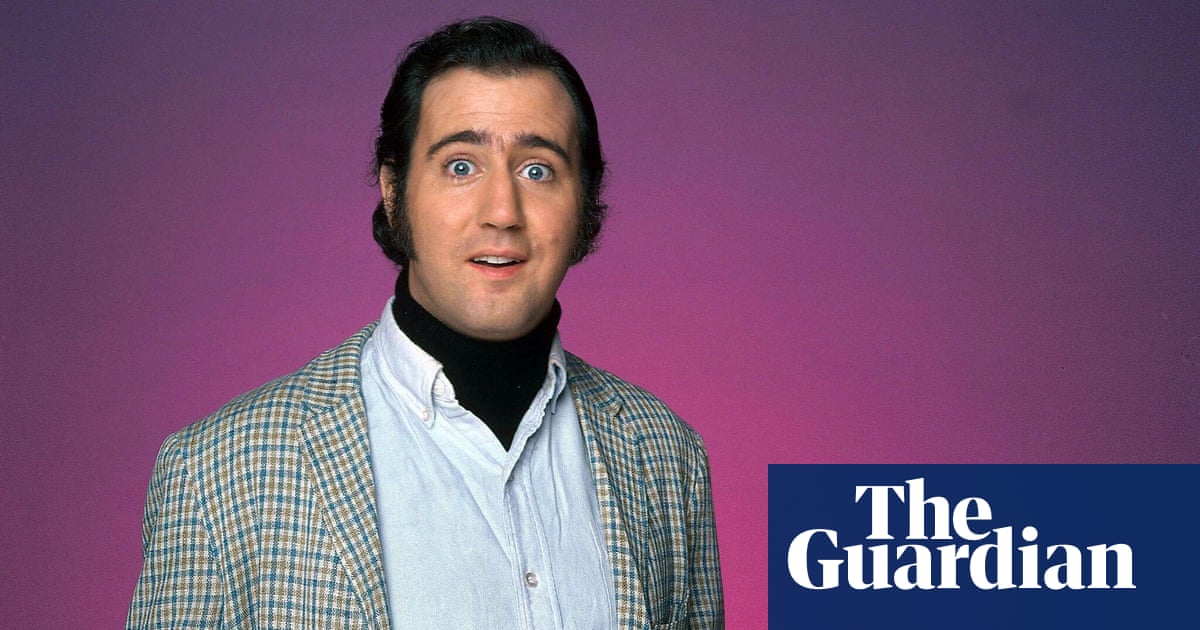

The stereotype of comedians is that they’re compulsively “on”, finding it difficult to revert to normal off-stage behavior when so much of their life revolves around getting laughs from a crowd. That makes Andy Kaufman particularly unusual, even this many years later: he is a comedian who worked so hard to raise questions about whether or not he was “on” that those questions lingered well after his death.

The creator of characters such as Foreign Man, who would unexpectedly break into a spot-on Elvis impression; Latka Gravas, the sitcom version of that character he did for the beloved show Taxi; the grotesquely abusive lounge singer never-was Tony Clifton; and the misogynist woman-wrestling showboat named, uh, Andy Kaufman constructed so many clever hoaxes to house his work that many assumed he must not actually have died young at the age of 35. (Some of his collaborators insisted on perpetuating that illusion, though his death certificate is widely viewable.)

The new documentary Thank You Very Much isn’t strictly necessary to recount Kaufman’s legendary antics. He appears as a major figure in plenty of books and films, whether directly about his own life (including Man on the Moon, for which Jim Carrey inhabited Kaufman so deeply that he had his own Netflix documentary about his process) or chronicling the institutions he touched along the way (like just about any book covering the history of Saturday Night Live). Just last fall, Nicholas Braun joined Carrey in playing Kaufman on the big screen; he recreated the comedian’s famous Mighty Mouse bit, where Kaufman timidly puts on a recording of the Mighty Mouse theme song and gathers the nerve to lip-sync along with a single line, as it appeared on the premiere episode of SNL.

What Alex Braverman’s film tackles is the comprehensiveness of the Kaufman project, placing it in a proper and personal context. Kaufman, a longtime practitioner of transcendental meditation, seemed to find a form of spiritual enlightenment in his commitment as a comedian, and clearly put a lot of thought into this aspect of his work. (There’s even footage of a young Kaufman asking Maharishi Mahesh Yogi whether achieving a kind of inner peace would eliminate the need for entertainment and entertainers.) Perhaps more so than the entertaining but somewhat conventional Carrey-starring biopic, Thank You Very Much is also upfront about how alienating Kaufman could be – to audience members, to casual observers, even to co-workers – while at the same time never framing his work as pure endurance tests. There’s an evident glee in his blurring the lines between reality and fiction, even when he does his best to hide it under voices or makeup.

Thank You Very Much doesn’t depend on the same old clips, and watching all of this Kaufman footage emphasizes how inimitable the man was. Eventually, his performance-art take on comedy does start to reveal some descendants, if somewhat superficial ones. Kaufman’s Foreign Man shtick feels like it might have influenced early Adam Sandler, when his bizarre little voices and bursts of nonsense might have made audiences wonder if this is a near-amateur or a polished professional having a laugh (and in a way, it was both, though even early on, Sandler would give himself away with endearing little breaks in the facade). The later work of Tim Heidecker, where he plays “himself” in the ongoing (and weirdly intricate) On Cinema series and in a standup special that spoofs hacky comics by convincingly performing a certain type of familiar routine, has a clear Kaufman influence as well; it similarly requires more than passive consumption in order to fully appreciate the joke.

What’s more difficult to replicate is Kaufman’s dedication to his strangest whims. (When Tim Heidecker passes away, it will probably not kick off a 30-year ambiguity over whether he’s genuinely dead.) The closest we have to that is something weirder and scarier, a kind of inverse to Kaufman’s thoughtful deception. In place of comedians who prompt the audience to wonder whether or not to take him at face value, it is far more common to see comedians who prod their audience to question the very nature of reality around them, but with comedians as their truth-telling, regular folks, and essentially trustworthy guides. The most obvious example, of course, is Joe Rogan, who “admits” to not being an expert while using his approachability to steer his audience in the direction of rejecting medical science or promoting baseless conspiracy theories. But the flipping of Kaufman’s brilliant gambits, where uncertainty about reality remains but the comedian is your trusted guide through that uncertainty, could apply to any number of comedians who cultivate parasocial relationships with their loyal listeners. It’s like a lazy man’s version of Kaufman: all the questioning, none of the performance.

This allows the comedian to risk little while amassing followers; Kaufman repeatedly risked his reputation – as well as whatever following he had gathered from Taxi or SNL. It’s wild to consider that in 1982, Kaufman participated in a bit on SNL that had audience members calling in to decide whether he would continue to pop up on the show. He lost the vote, appeared once more, never again – despite the fact that some of his colleagues in the doc claim that he was double-crossed by producer Dick Ebersol, who had grown tired of his antics. You’d never know either away from Kaufman himself. Today, it’s far more common for comedians to simply court a persecution complex.

There’s a lovely clip showcased in Thank You Very Much where Kaufman offers a rare reassurance to his audience: “Don’t be afraid of what you don’t know.” Today, that kind of mantra might have an entirely different meaning, used to promote a false sense of expertise from entertainers: don’t hesitate to speak up about topics you know less than nothing about! Given that, the way Kaufman was able to use the unknown as the existential engine of his entire career now seems all the more miraculous.