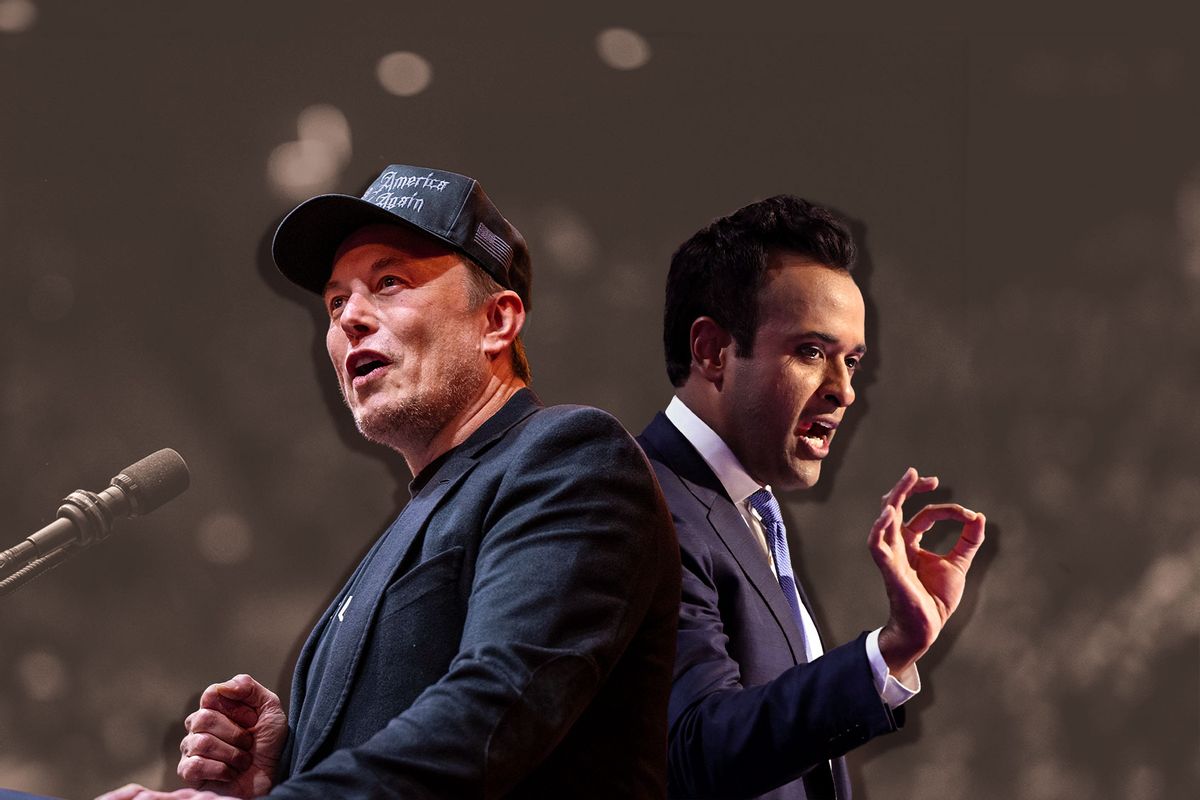

Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, the billionaires President-elect Donald Trump picked to lead the new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), have made their aspirations of slashing government spending clear, promising to bring a “chainsaw” to federal bureaucracy and costs.

To cut back on hundreds of billions in government spending, one approach Ramaswamy has suggested is eliminating programs that have lapsed spending authorizations despite still being funded by Congress, which include veterans’ healthcare services, housing assistance and the Justice Department. But not only does that proposal misunderstand the function and role of funding authorization in Congress, the lack of authorization doesn’t indicate wasteful expenditures, federal fiscal policy experts told Salon.

“They have a fundamentally superficial understanding of what they’re doing,” argued Bobby Kogan, the senior director of federal budget policy at the Center for American Progress. “They have a meme-level understanding. ‘Let’s get rid of unauthorized spending’ is the sort of thing that you might see in a Facebook meme.”

Ramaswamy and Musk expanded on that suggestion in a Wall Street Journal op-ed published Wednesday, outlining the newly minted out-of-government advisory commission’s plans for reducing excess spending. DOGE, they wrote, will target some $500 billion in annual federal expenditures that “are unauthorized by Congress or being used in ways that Congress never intended” in an effort to help “end” federal overspending.

But the notion that any spending is not approved by Congress or used outside of how the legislative body intends is “inaccurate,” said David Reich, a senior fellow at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. The Constitution requires Congress to authorize any and all government spending, which it does through funding bills, or appropriations.

“For anything the federal government is spending, there’s going to be an appropriation,” Reich told Salon in a phone interview. “It could be an annual appropriation. It could be an appropriation and authorizing law, but Congress will have authorized that expenditure.”

The authorization that Musk and Ramaswamy take up actually refers to an internal House of Representative’s rule that creates a separate process for authorization and appropriations, experts said.

Authorizing committees in the House make laws dictating provisions for the creation of agencies and their functions, which include “aspirational-level” provisions for how funds can be used like requirements for eligibility to receive that funding and stipulations on its use, Kogan explained in a phone interview, and the authorization is usually temporary to allow the committees to reevaluate those details over time.

“For a while it was a very common practice for authorizing legislation to say, ‘And there is hereby authorized to be appropriated X dollars in year one and Y dollars in year two’ and so forth,” Reich said.

But the House’s use of that language has lessened in recent years, and the chamber often waives the rule, explicitly or implicitly, by considering the funding bills, which it does “often completely consistent with what the authorizing law does,” he added, calling the authorization of funding via authorizing laws a “technical step.”

For programs where Congress has allowed its authorization to lapse, appropriations legislation covers it. Instead of needing two laws — an authorizing law that approves funding for an agency and another to actually allocate those funds — Congress only passes the appropriation, which then gives the program the authority to spend its funding, according to The Washington Post.

In their op-ed, Musk and Ramaswamy pointed to $535 million allocated to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, $1.5 billion for “grants to international organizations” and nearly $300 million allocated to “progressive groups like Planned Parenthood” as examples of excess spending that could be cut, appearing to cite figures from a Congressional Budget Office report on programs with unauthorized funds.

But Kent Smetters, the faculty director of the Penn Wharton Budget Model and a University of Pennsylvania Wharton School professor of business, economics and public policy, told Salon that these unauthorized funds don’t inherently amount to wasteful or excess spending either.

“In practice, unauthorized funds give a federal agency more flexibility to direct funds toward the needs that the agency sees as a higher priority at any point in time,” he said in an email, adding that “unauthorized funds are probably a bit more efficient because an agency might have more information about immediate needs after the funds were appropriated by Congress at a more aggregate level.”

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Programs without separate spending authorization amount to more than $516 billion of the budget, with the 10 largest programs comprising $380 billion of that share, according to a report from the Congressional Budget Office. Health care for veterans has the largest amount of “unauthorized” government spending, coming in at $119.1 billion. Funding for other programs like housing assistance under the 1998 Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act, and government entities like the State Department and Justice Department would, in theory, be on the chopping block, per Ramaswamy and Musk’s suggestions.

Still, as an out-of-government entity, DOGE can only make recommendations to Congress for ways to pare down the federal budget. “Congress will still decide whether authorized or unauthorized programs get funding,” Smetters said. “It is not up to the discretion of the White House.”

While policymakers have room to eliminate excess federal spending in bipartisan ways, Kogan said, the amount of wasteful government spending is far smaller than what Ramaswamy and Musk suggest.

“People have this idea of just huge and absurd amounts of government waste, and it’s just not borne out in the data,” he said.

Two-thirds of federal spending is mandatory, while the remaining discretionary spending largely goes toward defense. Over 70% of the nation’s non-interest spending is public benefits to Americans, like Social Security, SNAP, WIC, Medicaid and Medicare, Kogan said, and “by definition, if you’re cutting those, you’re cutting aid to people.”

“I think a lot of this comes down to people saying, ‘Well, I just don’t want us to do that program, and that’s fine,” he said, adding: “That is a stance someone can take, but it is flatly incorrect to pretend the money we give to states to help them make sure that kids with disabilities have enough money to succeed — that’s not waste. You might not like the program, but is just not waste.”

Read more

about the Department of Government Efficiency