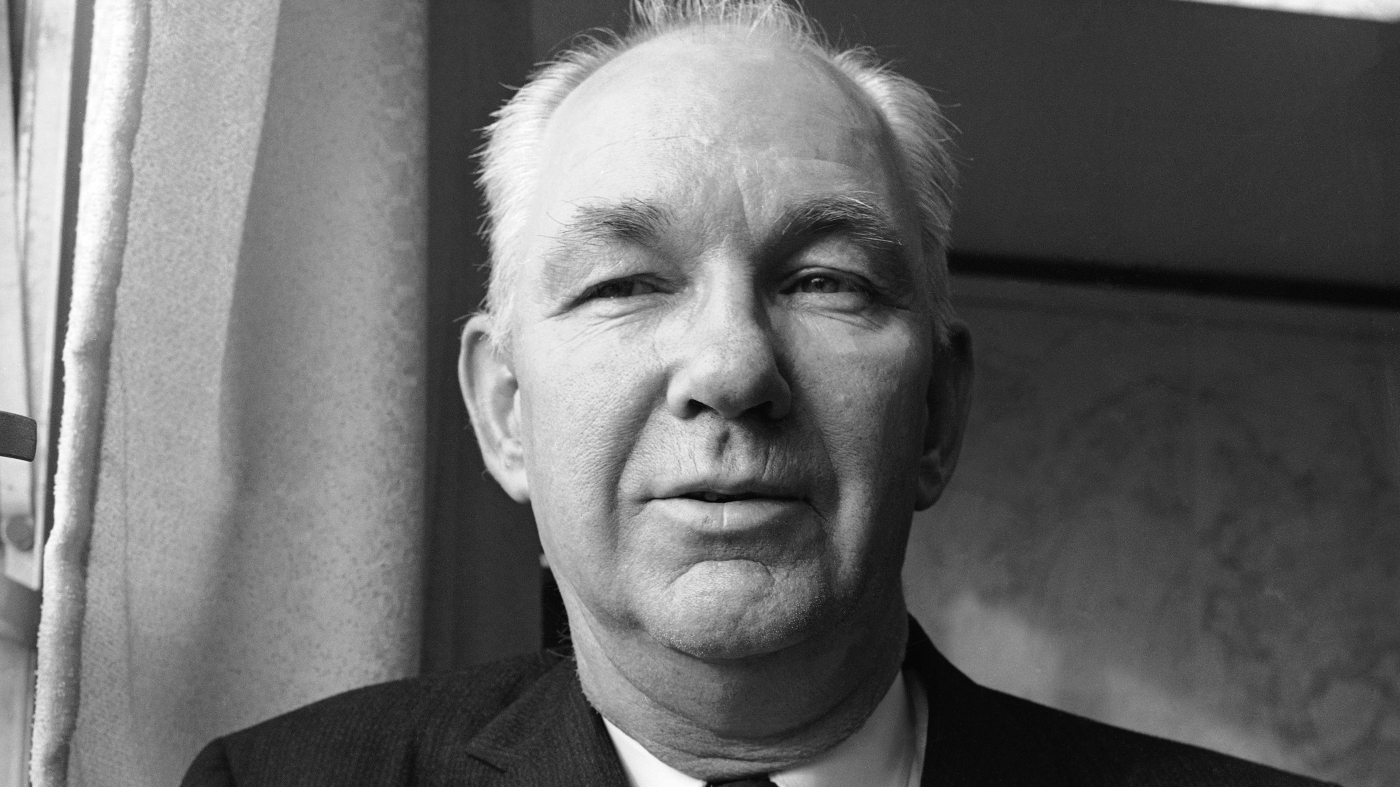

Justice Samuel Alito sits during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021. (Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images)

On Friday evening, just as reporters were logging off, the Supreme Court let slip a clue about whether it would take up cases that could determine the outcome of a close election in the coming weeks. Specifically, the hint came in a statement from Justice Samuel Alito. Spoiler: He’s open to it.

Alito’s missive came as the Supreme Court declined to take up a case over mail-in ballots in Pennsylvania. The Republican National Committee had asked the court to throw out a Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision allowing voters who had forgotten to place their mail-in ballot into a secrecy envelope to vote a provisional ballot. By declining to weigh in, the Supreme Court allowed some valid Pennsylvania voters who made a mistake in returning their mail-in ballots to still vote. The RNC had asked the US Supreme Court to stop them.

In response, the justices unanimously declined to disenfranchise these voters and created the impression of a win for Democrats and more expansive voting rights. Technically, this is true. But as a signal of whether the justices intend to meddle in the outcome of the election, the message was muddled by Alito’s writing.

Typically, the justices wouldn’t have considered such a case, because the Supreme Court isn’t supposed to second guess state court interpretations of a state law. But these are not normal times. Last year, the justices decided that second-guessing state courts was within their remit if the state law they were interpreting was election-related. In Moore v. Harper, the Supreme Court gave itself the authority to intervene in state election law matters if a state court’s decision “transgress[ed] the ordinary bounds of judicial review” at the expense of state legislative power. It’s a vague and untested standard, and this is the first election under this new precedent. The Supreme Court now has become a Sword of Damocles hanging over every state court decision concerning election procedures.

The Supreme Court now has become a Sword of Damocles hanging over every state court decision concerning election procedures.

In a statement accompanying the court’s order, Alito agreed with the rest of the justices not to take the case but chalked it up to the facts of the case, which he said constrained the court’s ability to give the RNC their requested relief of banning provisional ballots for spoiled mail-in ballots. Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch joined Alito’s statement. In the past, problems with the facts have not stopped the court’s conservative wing from taking on and deciding any case it wanted to. There’s the website designer who wanted to discriminate against a client who didn’t exist; the football coach who claimed he prayed alone when pictures showed him surrounded by players; and the case against President Joe Biden’s student loan forgiveness plans on behalf of an entity that wanted nothing to do with the case. The Roberts court’s forbearance is not something to take for granted. So was the show of restraint with the Pennsylvania case a sign that the justices will not become involved in the 2024 election?

Probably not.

Alito signaled that he and his two colleagues might reopen this specific dispute and others like it in the coming weeks if another case were presented. He called the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision “controversial” and the issue at stake “a matter of considerable importance.” As legal journalist Chris Geidner noted, this language is “a sure signal from the trio to the RNC, Donald Trump, and other possible litigants” and “clearly a set up.” Should Trump or his allies want to bring a new suit after the election, at least three justices would be open to taking the case. The question is, would a majority be willing to, as this case asked, deny people the right to vote? One framework for looking at a possible answer is by comparing the 2000 election to the 2020 election.

In 2000, the presidential election came down to a few thousand votes in Florida. It wasn’t clear who the winner would ultimately be if all of Florida’s votes were counted, but by mid-December, George W. Bush held a lead of 537 votes. The Florida Supreme Court had ordered a statewide recount of certain ballots, so the Bush campaign asked the Supreme Court to intervene. So when the justices halted the recount in a 5-4 decision, they handed the election to Bush in Bush v. Gore. In effect, they picked the president in what was a tossup situation.

In 2020, on the other hand, there were many entreaties for the federal courts, including the Supreme Court, to throw out ballots and hand the election to President Donald Trump. The efforts to contest the election were coming days and even weeks after it was clear that, with almost every swing state declaring Joe Biden the winner, this was not an undecided election. It was, barring very significant judicial meddling, an insurmountable lead, and despite his protestations, Trump had lost. In such a situation, the Supreme Court stepping in would have risked the court’s reputation. Why help Trump when it would only have given Biden, who would become president, a very good reason to consider court reform?

If tomorrow’s results look like a Bush v. Gore scenario, particularly if the single swing state of Pennsylvania looks like the new Florida, the court’s right flank may be faced with the opportunity to help in Trump’s election. After all, the court has taken multiple steps to help Trump retake the White House, most notably by scuttling his criminal trial over his involvement in the January 6 insurrection. They have also shown a willingness to help the Republican Party in their recent decision to allow Virginia to remove voters from the rolls in a manner contrary to federal law. Interfering again would be a continuation, not an aberration.

But if tomorrow’s results look more like 2020’s, and within a few days, Harris is the clear winner, a majority of the justices might find it unwise to stick their necks out for Trump. Famously, Trump doesn’t like to be associated with “losers.” The justices may feel the same way.