Two Japanese self-help books, whose Korean titles translate as “The low-consumption life” and “The monk’s way of cleaning,” are gaining popularity among readers seeking a sense of calm in a fast-paced, consumption-driven society. Both suggest that happiness can be rediscovered not through acquiring more, but through consciously spending less and clearing unnecessary things from life.

“The reason I prefer a low-consumption lifestyle is that it allows me to keep asking what truly makes me happy,” author Kazenotami (pen name) wrote in “The low-consumption life.” “I am convinced that I feel happiness far more easily now than when I used to spend money carelessly.”

“In Zen Buddhism, happiness doesn’t come from acquiring something new, but from letting go of what you don’t need,” said Shunmyo Masuno, a Zen priest and author of “The monk’s way of cleaning.”

Rediscovering happiness through low-consumption living

Shoppers browse at Lotte Mart in central Seoul, Oct. 29. Newsis

Unlike traditional guides that emphasize frugality or efficiency, Kazenotami’s “The low-consumption life” begins with practical steps but extends to redefining what it means to live meaningfully. Since its release less than two months ago, the book has sold more than 20,000 copies. Masuno’s “The monk’s way of cleaning” also saw strong sales, going into its second print within a month.

For Kazenotami, low consumption is not about endurance or self-denial. “Living with fewer things and less money isn’t about patience — it’s about returning to your true self,” she said. The author encourages readers to examine unconscious spending and ask what truly brings satisfaction.

She suggests, for instance, not simply avoiding cafes to save money, but asking, “What exactly do I enjoy about going to a cafe?” or “Can I recreate that feeling without spending money?” One of her key practices is the “zero-yen day,” which challenges the assumption that enjoyment always requires spending.

“A ‘zero-yen day’ isn’t just about not buying anything,” the author said. “It helps overturn the belief that fun requires money. Reading an unfinished book, taking a walk without your phone, or cleaning a neglected corner of your home can make the day feel richer.”

Kazenotami also promotes methods such as budgeting expenditure at the beginning of the month and alternating between modest and indulgent living toward the month’s end.

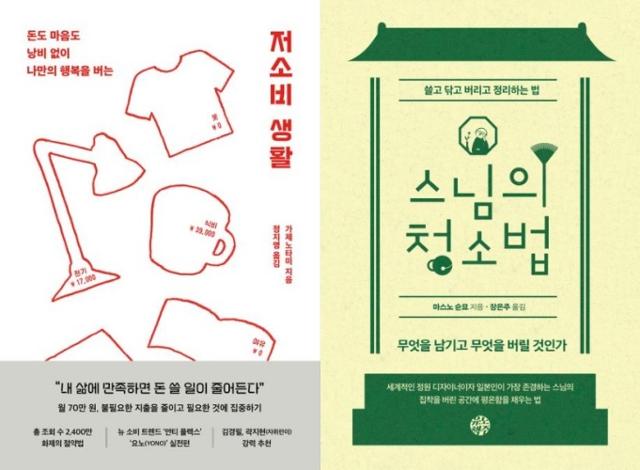

Front covers of “The low-consumption life” and “The monk’s way of cleaning” / Courtesy of each publisher

A single-person household, she lives comfortably on about 700,000 won ($500) per month, including 500,000 won in rent. Her home lacks common appliances such as a microwave, refrigerator, washing machine, bed, or storage furniture. She buys only enough food for the day, does laundry by hand, and owns around 10 clothing items in total.

Despite this simplicity, she feels a deeper sense of peace and freedom than when she spent more than twice as much while working in Tokyo. After leaving her corporate job in her mid-30s, she now works as a freelance YouTuber.

“Before, I thought spending money everywhere was freedom,” she said. “But I realized true freedom is spending just the right amount on what truly matters. When happiness feels out of reach, trying a low-consumption lifestyle might help you regain your sense of joy.”

Cleaning as spiritual practice

Shunmyo Masuno / Courtesy of Uknow Books

For Masuno, chief priest of Kenkoji Temple and a renowned garden designer, every day begins at 5 a.m. with cleaning. He sweeps the garden and wipes the temple’s wooden corridors. “Cleaning is a form of spiritual training,” he said, urging everyone to spend at least five minutes a day cleaning, no matter how busy they are.

“In Zen, there’s a saying: ‘First, cleaning; second, faith,’” Masuno explained. “After cleaning, everyone feels refreshed — not just because the space is clean, but because the dust and dirt inside the heart are also gone.”

Cleaning, he said, is closely tied to letting go of attachment. In an age when social media constantly fuels consumer desire, this is not easy. “Ask yourself: ‘Is this truly necessary?’ ‘Would it just be nice to have?’ or ‘Would it make my life feel dreamy?’” he said. “When you think this way, only what’s truly essential remains.”

He also criticizes the modern habit of obsessively searching for cleaning gadgets before cleaning itself. “Monks use only four tools: a broom, a cloth, a duster, and a bucket,” he said. “Cleaning is about moving your body and investing your time — not relying on tools or detergents.”

“Cleaning isn’t something you do because others can see it, nor something you can neglect because it’s hidden,” he said. “It’s an act for yourself.”

By removing unnecessary items and wiping away dirt, Masuno said, one can free oneself from greed and vanity. “When that happens, your true self — once hidden under thick clouds — reappears. In that simple, clear state, you rediscover who you really are.”

That is why he advises those facing a life crossroads not to rush into drastic changes, but to start by cleaning, little by little.

At temple entrances, signs often read “Look carefully at your own feet” and “Arrange your shoes neatly.” Masuno interprets this as a reminder: “Focus on what you can do right now, with sincerity.”

This article from the Hankook Ilbo, the sister publication of The Korea Times, is translated by a generative AI system and edited by The Korea Times.