Foodways are embedded throughout the museum, too. Smith pointed out a display that holds artifacts of a Chinese workers camp: a ginger jar, a tea cup, a rice bowl, a glazed stoneware jar that stored vinegars and sauces.

Even though Chinese workers made up 90% of the labor force for the Central Pacific Railroad, they were in segregated camps, according to Smith.

“The Chinese railroad workers didn’t get the same pay or food allowances that their Irish and other counterparts did,” he said.

Even this small display illustrates the racism baked into the building of the railroads: the chasm between people who owned the railroads and the people who worked on them.

The museum also has a sleeper car on a rocker to simulate the feeling of being on a train. It’s set up to show how the car would look both during the day and in the evening.

“During the day, the upper berths would be folded up. The lower berths serve as comfy seats,” said Smith.

At night, porters would unfold the upper berths and convert the seats to beds. Smith pointed to a little button passengers could push to call a porter.

Next to the sleeper car is a 1937 Cochiti dining car, which ran on Santa Fe’s Super Chief train between Chicago and Los Angeles.

“That gives us a chance to talk about what it was like to dine on a train during the golden era of rail travel,” Smith said.

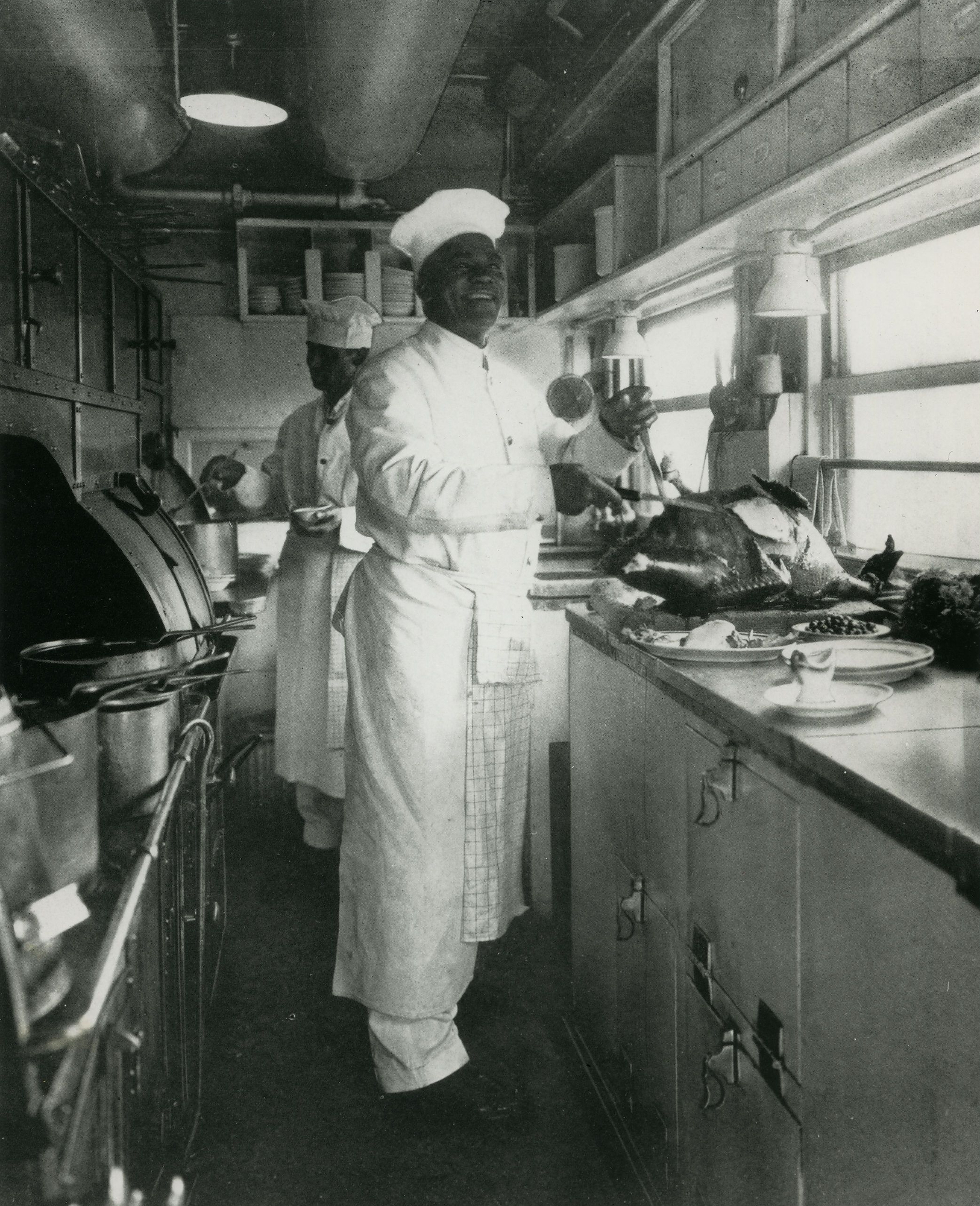

In the narrow galley kitchen, it’s hard to imagine all the people needed to prepare three gourmet meals a day for 50 people.

“The chef, people doing prep, mise-en-place,” Smith enumerated. “You’d have to find a cadence to work within the space. A lot of gleaming stainless steel-like surfaces — knives and graters and colanders and big soup pots.”

Called to the dining room by chimes, passengers would sit among abundant flower arrangements and intricate Art Deco metalwork. They ate at tables with tablecloths and off of china with patterns that reflected the route: poppies in California and animal images inspired by Native American art in the Southwest.

Docent Allen Blum shared a menu for the Super Chief, including “ripe California colossal olives, grapefruit, orange and raisin fruit, swordfish steak, and poached salmon.”

Menus often reflected cuisines and ingredients along the route. Blum said the Super Chief carried politicians and stars from Walt Disney to Jack Benny to Marilyn Monroe.

“This was definitely considered first class,” he said.

Passengers on dining cars came to expect attentive service — one waiter per two tables. Smith explained that the businessman best known for railroad dining cars was George Pullman. He built and owned luxury train cars to appeal to passengers who wanted to travel in style, and he leased his cars to the railroads.

Smith said Pullman was a master at branding.

“Pullman is creating the romance of train travel,” he added. “To ride on a Pullman car means something, and this feeds his ability to lease these cars to the railroads.”

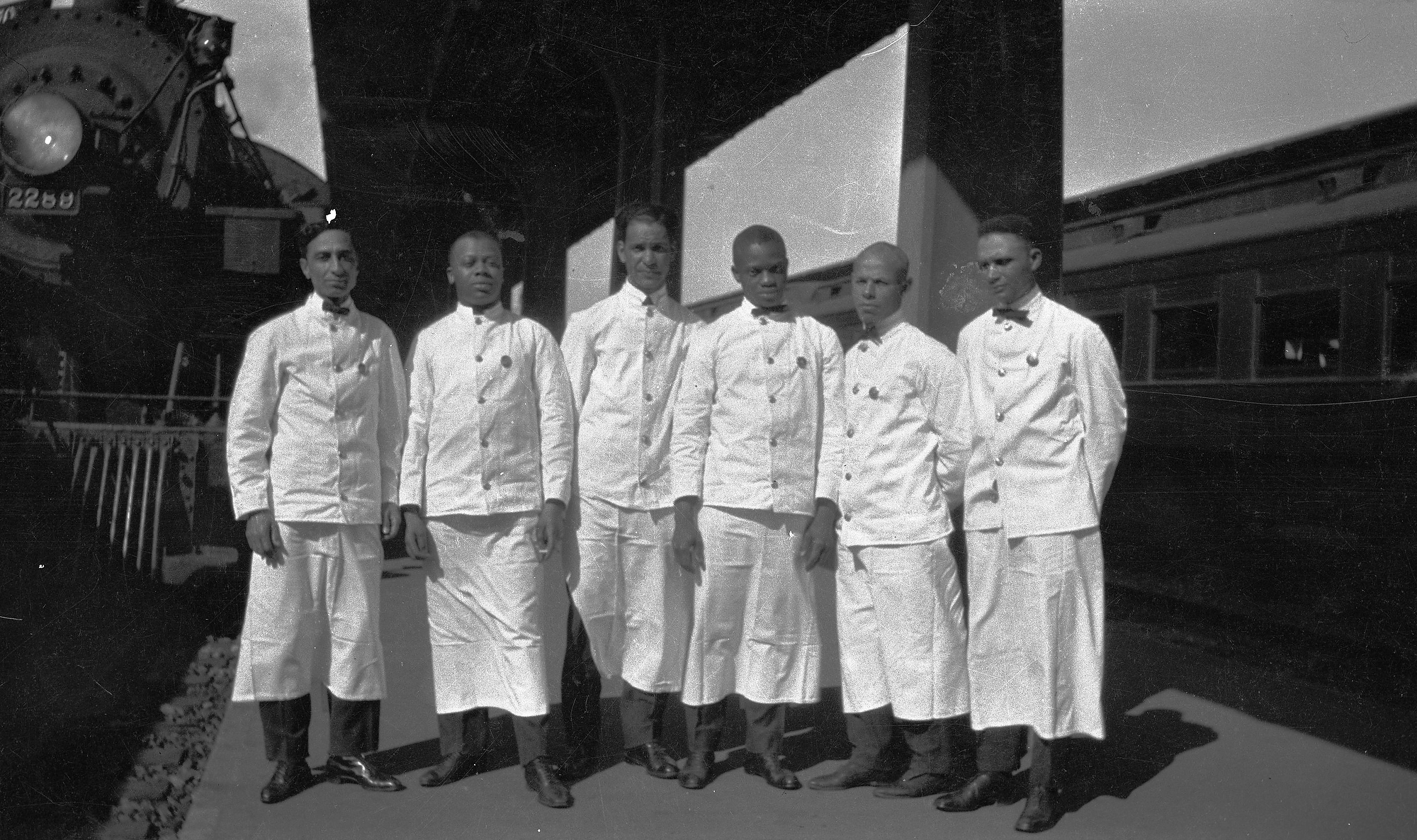

But Pullman built his business on the backs of the Black service workers he hired.

“It was a luxurious experience, but a completely racialized experience,” said Susan Anderson, history curator at the California African American Museum. “From the appointment of the sleeping area to the dining car to the cuisine and the meals, the way that you were waited on, all of that was just premium. And all of it, on the Pullman cars, was provided by Black labor.”

Engines of resistance

White men held positions like engineer and conductor. The servant-type jobs — porter, steward, cook, maid and waiter — were reserved for Black people.

“George Pullman and the Pullman Company were explicit about this,” Anderson said. “They wanted white people to be waited on by Black people because, in our history, racism conflated being a slave or being a servant with being Black.”

Porters who did everything from turning down beds, carrying luggage and serving food were usually not addressed by their names. They were called “George” after Pullman.

Anderson said the subjugation of Black workers was a direct reflection of the way the U.S. economy was organized.

“So, that’s U.S. history. But Black history is that they took these positions and they made the most out of them, and they used them to the advantage of their own people and their own families,” she said.

Many Black people saw railroad jobs as opportunities to broaden their horizons, bring money back home or leave Southern states altogether and move their families elsewhere.

“People who worked for the railroad got a lot of respect in the community,” said Anderson.

Her own family has a connection to railroad history. Anderson’s maternal great-grandfather was a chef on the railroad. His name was Edward Wilcox and his family was originally from Louisiana.

“They came to West Oakland in the late 19th century,” Anderson said. “They actually established a church in West Oakland. It’s still there, Bethlehem Lutheran Church. And that enclave was partly like a labor reserve for the Southern Pacific Railroad.”

By 1926, the Pullman Company was the largest single employer of African American workers in the country, with over 10,000 porters and 200 maids.

According to Anderson, a lot of intellectuals worked as porters or waiters.

“There were college men who had no other employment opportunities in a racist economy,” she said.

The railroad workers left a big legacy in American civic and cultural life. In his autobiography, Malcolm X wrote about selling sandwiches on trains. Renowned photographer Gordon Parks waited tables in dining cars. Thurgood Marshall, Willie Brown, Tom Bradley and Dionne Warwick had fathers who were porters.

Railroad workers networked with each other across the country, sharing copies of Black-owned newspapers and other literature, including The Messenger, a political and literary magazine for Black people that was founded by A. Phillip Randolph, an influential civil rights activist and labor organizer.

“And they began the effort to organize so that they could demand better wages, better working conditions for themselves, better hours,” Anderson said.

In an oral history archived at the African American Museum & Library at Oakland, former Oakland-based Pullman porter Cottrell Laurence (C.L.) Dellums said, “There was no limit on the number of hours. The company unilaterally set up the operation of the runs.”

Dellums, whose late nephew, Ron Dellums, was a California congressman and former Oakland mayor, started working for Pullman in 1924. He said the salary at the time was $60 a month. Workloads for the porters was from 300 to over 400 hours a month.

“And they provided what we said was just enough rest between trips for the porter to be able to make one more trip,” Dellums said in the audio recording. “Anybody could take the porter’s job. Not only any kind of Pullman official — from the lowest to the highest — could take his job. Anybody traveling as a passenger, even though it might be the first trip they’ve ever been on a train, they could write him up and get him fired.”

Kept out of the American Railway Union, Black workers founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters & Maids in 1925. Dellums began signing up workers for the union despite the risks.

“I never heard of a war that there weren’t battles. And never, never heard of a battle without casualties … But I will be heard from. And so I did. And sure enough, of course, they did discharge me,” Dellums said.

He eventually became one of the union’s vice presidents.

It took years, but the Brotherhood became the first Black union to be recognized by the American Federation of Labor. In 1937, they got a contract with Pullman, the first in history between a Black union and a large U.S. company. The union established an eight-hour work day, regulated work schedules and increased pay.

The Brotherhood influenced much more than service work on railroads. They were on the ground for many efforts during the civil rights movement, including the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington.

How railroads changed what and how we eat

Along the California Zephyr’s route through the outskirts of Sacramento, intricate irrigation systems and crops in perfect rows reveal the railroad’s impact on agriculture.

Archivist Benjamin Jenkins has written about the railroad’s impact on what we eat in his book, Octopus’s Garden: How Railroads and Citrus Transformed Southern California.

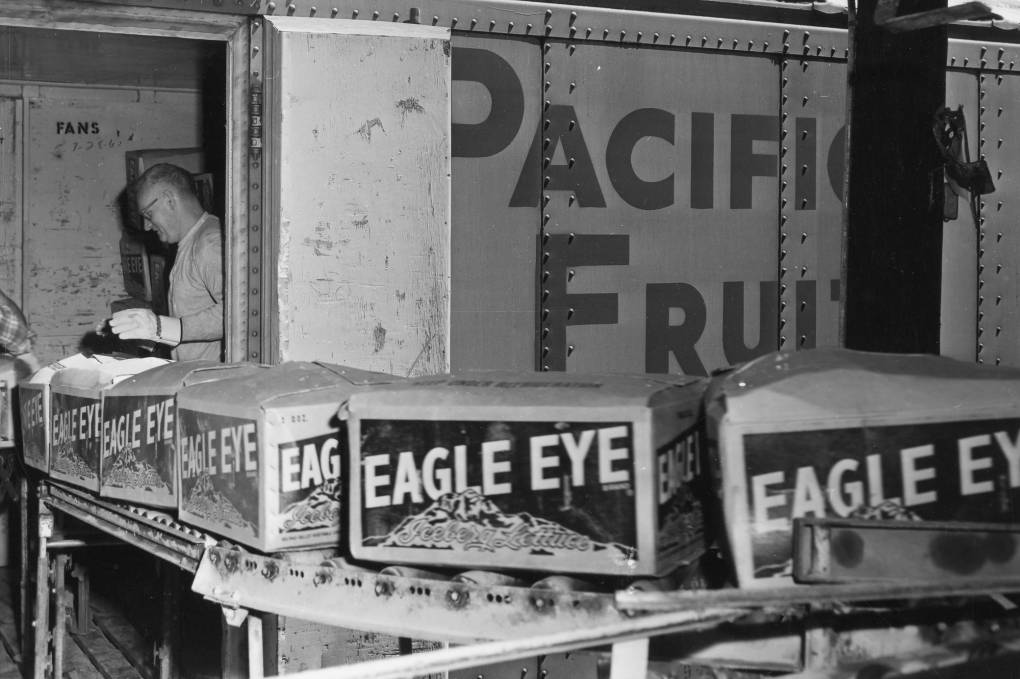

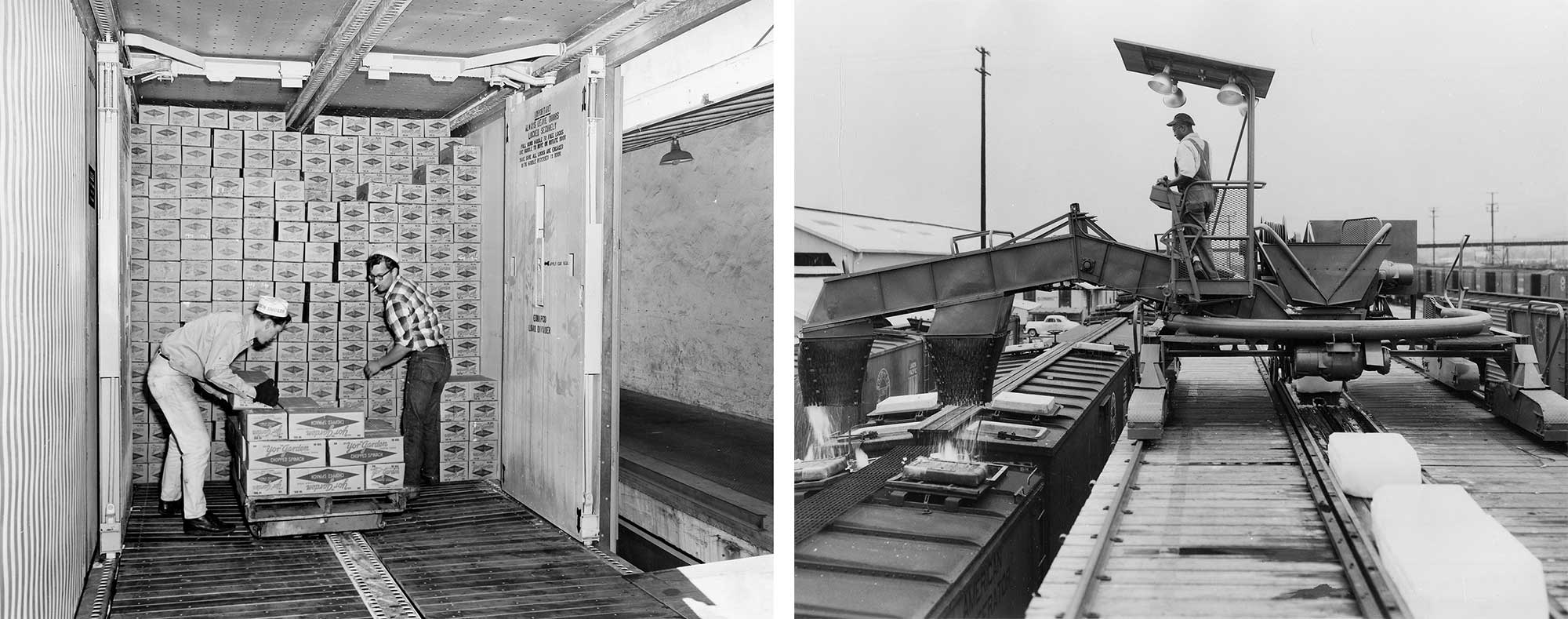

The first entire railroad car full of oranges left Los Angeles for the Midwest in 1877, Jenkins told KQED. The oranges traveled on a refrigerator car packed with ice.

“It had to be re-iced 10 times going across the desert and the Badlands to make sure that the fruit didn’t spoil,” he said.

California’s produce industry took off a decade later.

“But once it starts, it really never looks back,” Jenkins said. “So the explosion of new people, new crops as a result of the railroad bringing them in, and then shipping the goods out is just utterly transformative for California.”

Railroads built “spur lines” off the main lines to access huge parts of the state.