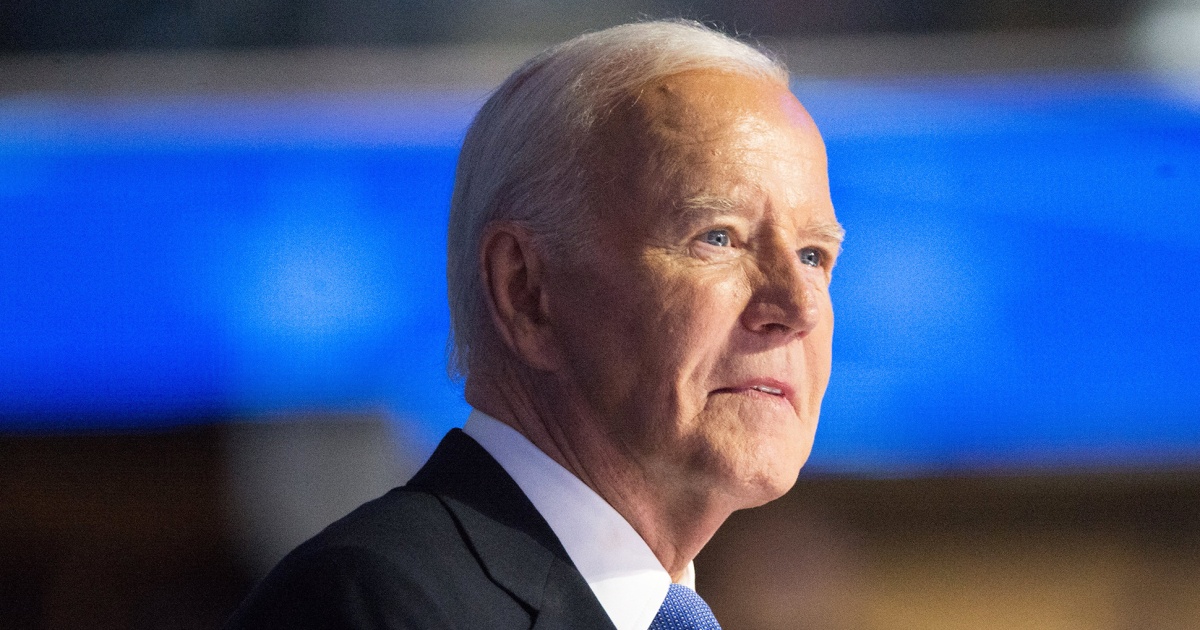

As disturbing as it was to read, an August report by the civil protection unit under President Joe Biden offered Texas’ criminal-justice reform community a sliver of hope.

It confirmed some advocates’ pressing concerns.

The Texas Juvenile Justice Department “uses excessive force on children” and “fails to prevent staff from sexually abusing children,” the 73-page assessment from the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division said.

“Body-worn camera video reportedly showed one of the staff slamming a child’s head into a brick pillar, knocking him unconscious,” said one section.

“Our review of hundreds of investigation reports from the Office of Inspector General shows a pervasive atmosphere of sexual abuse, grooming, and lack of staff accountability and training” at the department, where around 800 children from the ages of 10 to 18 are housed in Texas, added another.

In August, the weight of the federal government loomed large. A lawsuit against the state was possible, should Texas refuse to address the “very severe and significant violations,” Kristen Clarke, the Assistant Attorney General of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division said at the time.

Then, the election happened.

As President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration nears, advocates are waiting to see if his administration will pressure TJJD to correct the failings found in the report. And have turned their sights to another avenue of potential reform: the freshly convened 89th Texas Legislature.

‘I’ll Leave It at That’

The federal report was the culmination of a three-year deep dive into TJJD’s five facilities and was launched after two advocacy groups lodged complaints about the conditions within the lockups. The department’s governing board has since largely dismissed the findings.

“I’m going to tell you — just from my personal experience — I don’t think it’s completely accurate,” former TJJD board chairman Scott Matthew said three weeks after the report was released, according to an archived video of the meeting. “I’ll leave it at that.”

The threats of violence, another department official insisted, come from the children.

“To provide some contrast, most of the investigations we do in (the office of the inspector general) are actually juvenile offenders assaulting our staff to varying degrees of injury and severity,” TJJD OIG Chief Daniel Guajardo told the board. “I don’t have any examples or evidence to present to the board that youth are experiencing any beatings while they’re confined at TJJD at this time.”

Shandra Carter, the department’s executive director, partially pinned the agency’s shortcomings on staffing levels and limitations imposed during the COVID pandemic.

“When the site visits began, we were in the worst staffing crisis of TJJD and (the former Texas Youth Commission) history,” she told the board in August. “We had facilities at double their population of what we could safely manage.”

The investigation was also dated, they added, and the agency is under new leadership.

Carter, whose tenure began weeks before federal officials made their first site visit in 2022, said in August that, of the 48 recommendations listed in the DOJ’s report, 40 had been completed or were in progress. Department officials have been scant on details however, as the majority of discussions about the federal report occurred in executive session.

Carter also said that the department has surged its ranks, thanks in part to increased pay for potential and current officers. By late summer 2024, the number of full-time juvenile corrections officers had increased to about 850 from less than 650 when the federal site visits began, according to information Carter provided to the board.

Advocates, however, argue that the agency has been plagued with issues for years — a Dallas Morning News report from 2017 alleged near-crisis conditions inside the youth lockups — and problems highlighted in the report were not so simply resolved.

Jennifer Toon, the project director of the criminal justice advocacy group Lioness Justice Impacted Women’s Alliance, added that blaming children was a cheap cop-out by department officials.

“When they talk about how staff are in danger and these kids are so violent and just really putting the ownership on the kids again, it’s extremely frustrating,” she said. “I feel like someone who is just talking into the wind.”

During a board meeting in November, members discussed a video from one of the facilities that showed a juvenile assaulting an officer. Toon said what they didn’t discuss was what could have led up to that confrontation.

“It was a video that none of (the public) saw that day,” she said. “I can guarantee there was a reason. I understand that there are children with high needs and a lot of problematic violent behavior, but it is not unprovoked. Kids in crisis that are acting out, it is for a reason.”

Will the Trump Administration Weigh In?

Brett Merfish, the director of youth justice and the Juvenile Justice Project at Texas Appleseed — an advocacy group that promotes social and economic justice — said the timing of the report’s release three months before the presidential election wasn’t ideal. Sooner would have been better.

“I think it would have been harder for (the board) to discount it as being ‘outdated,’” she said. “If we had a Democratic administration coming in, or a non-Trump administration coming in, it would be fine. It’s not necessarily a partisan issue, but I think Trump is such a wildcard.”

But advocates for reform are well versed in being patient, and Merfish said the federal report could still prompt a lawsuit or consent decree.

“Nothing is known, right?” she said. “This issue has not gone away, and they are not going to formally dismiss it.”

“What happens now under this (incoming) administration, it’s a really mixed bag,” said Alycia Castillo, the associate director of policy at the Texas Civil Rights Project. “On one hand we do have an indication that things for criminal justice could be worse than they are now.”

Under Trump’s first term, watchdog groups sounded alarm bells after the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention struck an enforcement-heavy tone in 2018. The agency removed or buried language on its website that related to females in the detention system that emphasized family engagement or discussed scaling back solitary confinement, the Sunlight Foundation reported.

There is also Project 2025, the right-wing blueprint for the incoming administration. Trump tried to distance himself from the conservative roadmap before the election, but has installed some of its main contributors to key positions.

“It outlines a lot of reasons to be concerned that there is going to be a pretty intense era of ‘tough on crime’ and more marginalized people who are subject to criminalization,” said Castillo.

The former president is familiar with the criminal justice system — last week he was sentenced to an “unconditional discharge” in the New York hush money case in which he was found guilty of 34 counts of falsifying business records. Though he’ll face no further penalties, he’ll become the first president to have been sentenced for a criminal conviction — let alone felony convictions — when he’s sworn into office on Jan. 20.

Before that, he struck a bipartisan tone when he signed the First Step Act in 2018, legislation that sought to reduce recidivism and long-term incarceration in the federal corrections system.

“Everybody is just kind of wondering where he is going to land,” said Castillo.

Will State Legislators Push For Change?

Outside federal pressure is another option — state legislators.

“We think there are some things the Legislature can do this session to help with some of these conditions, regardless of what the DOJ does,” Merfish said.

Merfish and Texas Appleseed said three of their priorities they’re hoping to see make it into state law include requirements for children with mental health conditions in TJJD to receive a minimum amount of counseling; limits to how long a youth can remain in isolation; and limits to who gets sent to TJJD facilities.

Democratic lawmakers will also continue their push to completely dismantle the juvenile justice department during the 89th Texas Legislature, which gaveled in on Tuesday.

State Sen. Royce West, D-Dallas, has already filed a bill to create a state office of Youth Health and Safety that would close down the department’s facilities by 2028.

Although shuttering the agency is a long shot — the Legislature in 2023 allocated $200 million for new facilities and 200 additional beds — advocates for change are still hopeful that the spotlight on the department could lead to some significant reforms.

It’s not as quixotic as it sounds: Criminal-justice reform often creates strange bedfellows, as recently witnessed in the bipartisan effort to spare the life of death row inmate Robert Roberson.

State Rep. James Talarico, D-Austin, is part of a group of lawmakers on the Texas House Committee on Juvenile Justice and Family Issues, which tore into officials at the juvenile justice department in late August. His goal to dismantle the youth-incarceration system remains, regardless of who is president. At least the federal report got the attention of state lawmakers of both stripes, Talarico told The Barbed Wire.

“Maybe (the report) doesn’t move the leadership at TJJD, but it has moved lawmakers, and I hope that remains true,” he said.

When asked, neither the state juvenile justice department nor the Biden administration provided updates on any pending litigation. But the board has met in executive session to discuss potential litigation.

In its last meeting of 2024, the board gave initial approval to pursue a ground lease in Ellis County for a new facility. The agency also announced a new board president, Tarrant County Commissioner Manny Ramirez, whose appointment runs through 2027. Ramirez said in a social media post that he’ll work to make Texas’ juvenile justice department “the model for the rest of the nation.”

“Public safety will always remain the number one priority,” he added. “And working together we will provide the support and service that our partner agencies and committed youth deserve.”

Though uncertainty reigns, there was one morsel of recent good news from the advocates’ perspective. Weeks after the report, the department’s board approved a $34,000 raise for Carter, the executive director. But the state’s Legislative Budget Board later shot the pay raise down. (Carter’s current salary is about $238,000, according to the Texas Tribune’s salary database.)

The board later moved to direct its staff to “work through the legislative process” to secure Carter’s raise during the session. “I don’t know in what other space you can have a terrible performance report and get a raise,” Toon told The Barbed Wire. “It was just shocking and insulting when they had asked for it after the DOJ report. So, (the rejection) was a nice little gift to have received amongst still incredibly hard shit to hear. Because that felt validating.”