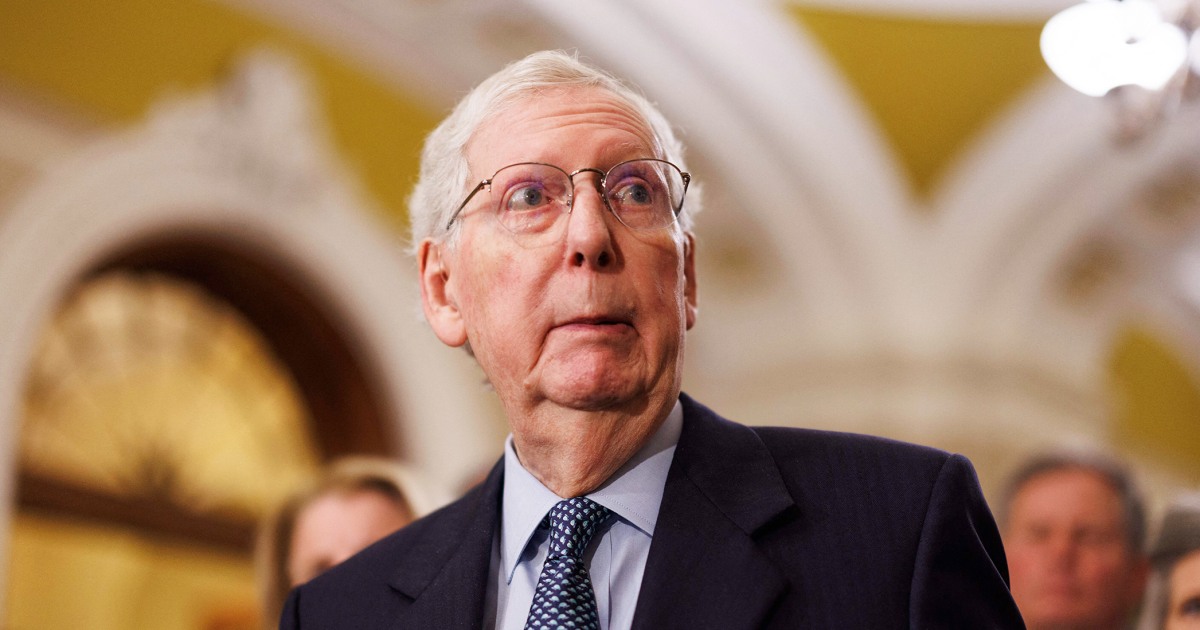

Democrats have little love for former Senate Republican Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. Over the years, the Kentucky senator infuriated Democrats with his blanket opposition to President Barack Obama’s agenda, his refusal to call out Russian meddling in the 2016 election and his failure to follow up on his condemnation of Donald Trump’s role in the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, along with countless examples of basic obstructionism.

But if Democratic lawmakers want to make it through the next four years, they are going to need to learn to think like their former antagonist.

McConnell played American politics like a cutthroat game in which the only goal was to win the next election. His laser focus on undermining the Democratic opposition was generally not good for the American public, and it didn’t always work. But his efforts did prove that a party in the minority can come back from a devastating defeat by simply refusing to cooperate.

He lived by the dictum that the job of the Senate minority leader is to become the majority leader.

He lived by the dictum that the job of the Senate minority leader is to become the majority leader, and it largely worked.

Faced with President-elect Donald Trump’s return to the White House, some Democrats have looked for ways to make common cause with some parts of his agenda. Some Senate Democrats, for example, have mentioned areas in which they could work with conspiracy theorist, anti-vaxxer and Trump’s Department of Health and Human Services pick Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Maryland Gov. Wes Moore, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, Georgia Sen. Jon Ossoff and New Jersey Rep. Josh Gottheimer, all Democrats, have said they hope to find common ground with Trump. Pennsylvania Sen. John Fetterman says he’s “not rooting against” the incoming president.

This is understandable. Democrats have long been more likely than Republicans to say they value compromise, and many Democratic officials looking at Trump’s sweep of the swing states in November are brainstorming ways to get back some of his voters.

But I’m wary of the efficacy here. Finding common ground with Trump means giving legitimacy to some of his unqualified and risky Cabinet picks. It undermines the election messaging that Trump was dangerous and a threat to democracy. And it will likely shift the Overton window in a more conservative direction in the long run, making it harder for Democrats to win in the future. After all, if Democrats are offering a light beer version of Republican policy, many voters will opt to just drink the strong stuff instead.

Republicans took a different approach after Obama’s election in 2008. On the night of his inauguration, a group that included pollster Frank Luntz and future House Speakers Paul Ryan and Kevin McCarthy met at a D.C. steakhouse and decided on a strategy of all-out opposition to Obama’s agenda, according to PBS Frontline. This approach is best remembered by McConnell’s infamous quote ahead of the 2010 midterms: “The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

McConnell showed how that approach worked in practice when it came to the fight over the Affordable Care Act. Obama and Senate Democrats worked hard to find the compromises that might get a Republican senator to support the health care reform bill, but McConnell and others made sure that didn’t happen.

“We worked very hard to keep our fingerprints off of these proposals,” McConnell told The Atlantic in 2011. “Because we thought — correctly, I think — that the only way the American people would know that a great debate was going on was if the measures were not bipartisan. When you hang the ‘bipartisan’ tag on something, the perception is that differences have been worked out, and there’s a broad agreement that that’s the way forward.”

Voters tend to assume the president is responsible for most things.

This works because most voters aren’t paying close attention to what’s going on in Washington. They tend to assume the president is responsible for most things (consider the 17% of voters in battleground states who blamed President Joe Biden for the overturning of Roe v. Wade) and they lean on heuristics to understand politics. Was the bill hundreds of pages long? Was the debate over it heated? Did it pass on party lines? Those are signals in the noise, even if they are sometimes misleading.

Starting Jan. 20, Democrats need to ensure that Trump owns everything that happens, and that Republicans own Trump. They need to force Republicans to take party-line votes to pass tax cuts for the wealthy, let ambitious progressive policy bills die from GOP infighting and decline to step in to rescue the Republican speaker when he can’t keep his own people in line.

And Democrats can also learn from McConnell’s failures. While the Republican leader was good at opposing Obama, he and other GOP leaders failed to come up with a compelling vision for what they would offer if returned to power. Obama wasn’t a one-term president, after all, and the ideological sameness of Republican contenders in 2016 allowed Trump to sweep in with a far different vision than even McConnell wanted.

Even if they stick together to oppose Trump’s agenda, Democrats need to do the hard work now of figuring out what they stand for, which ideas they can run on, win and then turn into policy that helps them win again.

McConnell was successful as a political leader because of his single-minded focus on the next election, but he didn’t seem to have much of a plan for the day after the election. Apart from tax cuts, more Supreme Court justices and rolling back the previous Democratic president’s policies, the elder statesman didn’t have a vision for the future of the country, and Trump stepped in to fill in the blanks.

Democrats don’t have that luxury. If they want to win again, they need to come up with a game plan for the next election — and the one after that.