Some economists will tell you that rational choice — the assumption that people have well-defined preferences and act optimally on the basis of those preferences — is the bedrock of our field, that anyone questioning that assumption isn’t doing real economics.

Some economists aren’t all that bright.

Rational choice is a simplifying assumption that can be very helpful for building models that help you think through some otherwise complex issues — and people who think that they’re being sophisticated by eschewing models are invariably fooling themselves; they’re implicitly engaging in theory without realizing it. But unless you’re an economist whose nose is so buried in equations that you never look out your window, you realize that people often act irrationally. And sometimes deviations from rationality have huge, real-world consequences.

Gambling is a classic example. Rationally, it’s a lose-lose proposition: The house always wins in the end, so you’re trading increased risk for a negative expected return. But casinos make money because gambling plays to our self-destructive instincts. There’s a huge literature on the psychology of gambling, and I’ve only skimmed the surface, but the major points seem clear. If you make a wager and you win, there’s a powerful impulse to make another wager; if that wager or the next goes bad, there’s a powerful impulse to bet again until you’ve made up your losses, which usually just digs the hole deeper.

And gambling can all too easily become addictive. True, it’s not a physical addiction, but that really doesn’t matter. A 2013 article in Scientific American put it this way:

Which is why I was struck by a recent Wall Street Journal report:

Indeed, there’s a lot of evidence that gambling — not just traditional forms like sports betting, but gambling on stocks and, yes, crypto — has become a national epidemic, possibly as serious in its own way as the opioid epidemic.

How did that happen? One way I’ve been thinking about it is that the story of financial addiction is, in an important way, the opposite of the story of cigarette smoking.

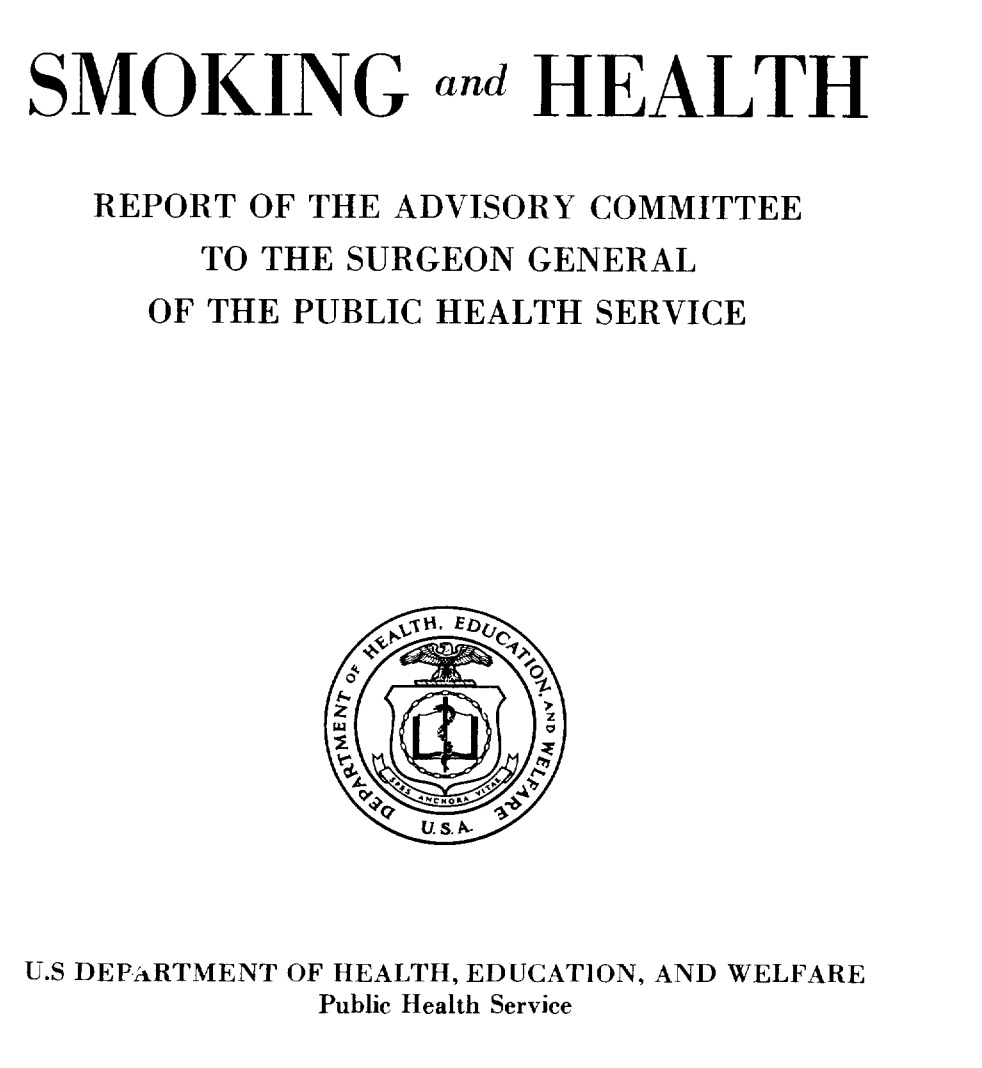

The Surgeon General’s report saying that smoking causes lung cancer and heart disease came out in 1964:

We did not, however, try to ban smoking: Policymakers had learned something from the debacle of Prohibition. What America engaged in, instead, was a long-term campaign against smoking that is one of history’s most successful examples of social engineering:

How did that campaign succeed? Nobody forced Americans to stop smoking. But cigarette ads were banned from TV, packages were forced to bear alarming (and true) warnings about the health risks, and being a smoker became increasingly difficult as more and more public spaces became smoke-free zones. These measures had a multiplier effect, too: Smokers diminished in number and were in effect pushed out of public view, with the result that smoking stopped being cool.

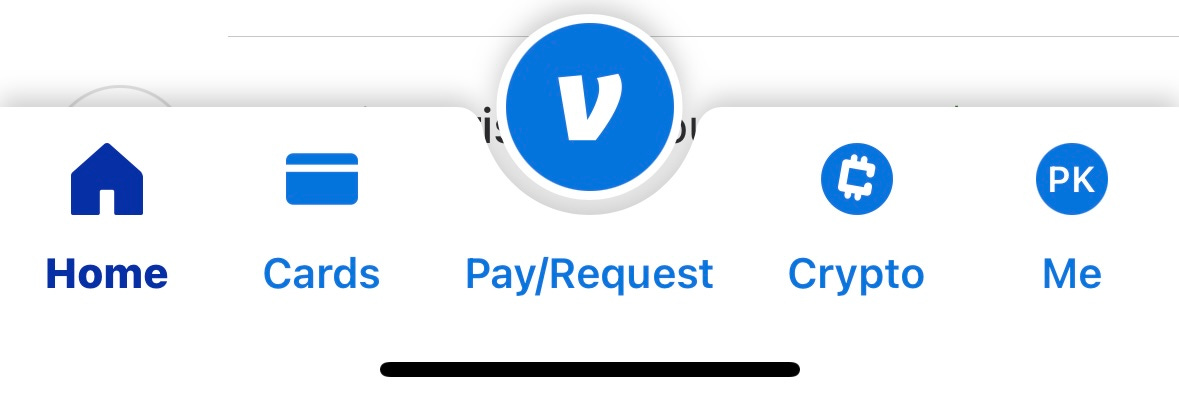

Compare that history with the more recent history of gambling, especially broadly defined to include speculation on stocks and crypto. You can’t find ads promoting smoking these days; you can’t avoid ads promoting stock speculation and especially crypto.

And I’m not just talking about conventional ads like the ones that played during the 2022 Super Bowl. De facto ads for what is effectively gambling are embedded in apps that many of us use for perfectly normal, non-speculative transactions. For example, like more than 80 million other people, I often use Venmo for small payments; even the sidewalk fruit stands in New York accept it. (I have never, however, used the app for Matt Gaetz-type activity.) Here’s what you see at the bottom of a Venmo smartphone screen:

If you tap the “crypto” icon it leads you to this:

And about those apps: if it has become ever harder to be a smoker, it has become ever easier to be a gambler. Once upon a time you had to physically go to the racetrack — if betting was legal even there, which in many cases it wasn’t — or at least call your bookie. Now you just tap your phone.

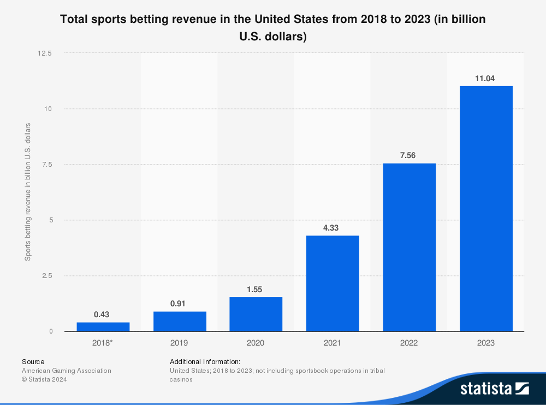

Policy has also played a role, notably in the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision to legalize sports betting. Since then that industry has exploded:

But the main way in which policy has contributed to America’s gambling epidemic isn’t what policymakers did, but what they didn’t do. As technology made gambling and speculation essentially frictionless, fueling the rise of predatory “limbic capitalism,” policy did nothing to protect Americans from their self-destructive instincts.

And while ordinary gambling can and does ruin people’s lives, gambling that takes the form of asset speculation can suck in far more people, because, as Robert Shiller pointed out long ago, widespread optimism about an asset’s price can for a while be self-fulfilling, because it initiates a “natural Ponzi scheme”:

The amplification mechanisms work through a sort of feedback loop; later in this chapter they will also be described as a type of naturally occurring Ponzi process. Investors, their confidence and expectations buoyed by past price increases, bid up stock prices further, thereby enticing more investors to do the same, so that the cycle repeats again and again, resulting in an amplified response to the original precipitating factors … Those who consistently predicted a decline became painfully aware of a loss of reputation from being so wrong so often. Since our satisfaction with our views of the world is part of our self-esteem and personal identity, it is natural for the formerly pessimistic to want to settle on a different view, or at least to present themselves to the public with a different theme. Thus the changed emotional environment will have an impact on their views—or certainly the expression of them—that is independent of any objective evidence supporting or refuting those views.

Shiller was talking about the stock bubble of the 90s — I still remember how big institutional investors finally surrendered and began buying dotcoms just in time to lose money in the crash. But replace “stock” with “crypto” and it reads exactly like a description of the past few years.

But wait — now I’m saying that crypto is used for gambling; didn’t I write a few days ago that it’s used for crime? Both can be true; it’s a floor wax AND a dessert topping.

Shiller’s analysis of bubbles still rings true, but with gambling on asset prices easier than ever, natural Ponzi schemes can run even longer and higher than in the past. And crypto, built on a foundation of technobabble and libertarian derp, is both a Ponzi scheme and a cult.

Furthermore, in addition to the way smartphones have made gambling, both overt and pretending to be investing, easier than ever, there’s a good case to be made that social media have increasingly turned the wisdom of crowds into the madness of crowds.

The veteran investor Cliff Asness has a new paper on how social media are degrading markets; I’ve had run-ins with Asness in the past, but I think he’s right about this:

But what if the crowd isn’t independent, but acts in unison? Well, this has the potential not just to destroy the magical crowd wisdom but to turn it into a negative. So, has there ever been a better vehicle for turning a wise, independent crowd into a coordinated clueless, even dangerous, mob than social media?

How much damage will the national gambling epidemic do? We won’t know the full extent of the damage until those natural Ponzi schemes collapse, which they will. Remember Dornbusch’s Law: “The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.”

But we’ve already seen the crypto piece of the gambling epidemic get so big that it’s seriously warping our politics.

Lots more to say about all this. For now let’s just say that a huge addiction problem snuck up on America while we weren’t paying attention.

MUSICAL CODA

There have been many, many covers of this J.J. Cale classic. This one, by a pair of blues sisters, is one of my favorites.